(5) The C-1, Automatic Pilot Course, Minneapolis Honeywell Regulators Company, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Graduates of these schools returned to their units to apply and share their new technical knowledge and skills.

During August and September 1944, the 315th's four bomb groups conducted their first bivouac training at Yankee Canyon near Raton, New Mexico. For five days, air and ground echelon personnel lived and operated under simulated wartime field conditions as specified in Second Air Force's Unit Bivouac Training Manual, dated 5 January 1944. During the bivouac, group personnel received training in camouflage, chemical warfare, close order drill, bomb dispersal, field sanitation, malaria control, mapping, infiltration techniques, gunnery, and defense against air attack. Members of the 16th Bomb Group vividly remembered what all the men of the 315th experienced during bivouac training.

We had to toughen up, the book said in large print. And Raton, NM is where the toughening up process took place. Toward the end of August we moved out to the bivouac area in Raton, a squadron at a time. We met the engineers (a little careless with their dynamite but otherwise O.K.) and we almost met every insect, snake, and lizard in the state of New Mexico. For diversion we ducked dive slugs on the infiltration course, walked through gas just to prove that our masks worked, and hiked around (but NOT to look at the scenery). The last night was a real thriller-diller. Until dark we made faces at each other from either side of the gully. Then somebody fired a flare and we mixed it up a bit. At midnight somebody called off the war but a few carried on a personal war until late in the morning. Dalhart looked just a little better after Raton.

Bivouac training was conducted periodically throughout the pre deployment period to insure all new personnel completed the training.

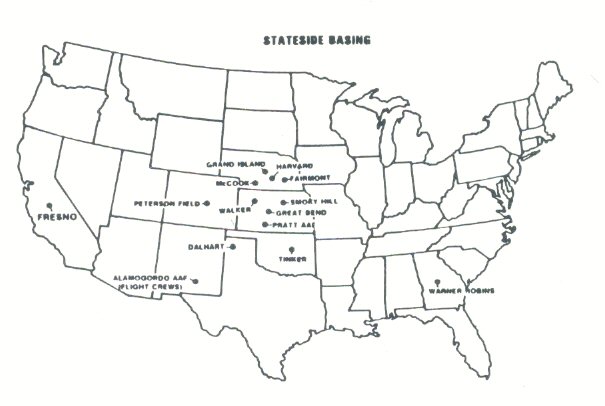

During August and September, ground echelons of the 16th, 501st, and 502nd Bomb Groups left Dalhart Field for operational training bases in Nebraska. The 16th was assigned to Fairmont AAF, Geneva, Nebraska, and the ground echelon arrived there on 15 August. The 501st arrived at Harvard AAF, Harvard, Nebraska, on 22 August. The 502nd reached its new home at Grand Island AAF, Grand Island, Nebraska, on 26 September. The group echelons paved the way for the arrival of their air echelons still on detached service at AAFSAT in Orlando, Florida. The bomb groups soon discovered their newly assigned bases were also occupied by other bomb groups still completing their final phase of pre deployment training. The 16th, 501st, and 502nd overlapped with the 504th, 505th, and 6th Bomb Groups (VH), respectively. This unit overlap had mixed effects.

The unit overlap benefited both tenant bomb groups at each base. For the 315th's bomb groups, all personnel immediately began to absorb the practical experiences of their more experienced counterparts. The accelerated training of 315th personnel was particularly evident in maintenance. Sergeant Edward H. Hering, an armament crew chief in the 501st Bomb Group at Harvard AAF, stated, "I learned more about the B-29 working with the crews of the 505th Bomb Group than I did in any technical school." By October the combined maintenance performance of the 502nd and 6th Bomb Groups at Grand Island AAF was so exemplary, the Commanding General of Second Air Force commended all personnel for their achievement in the number of hours flown per aircraft. Their success was largely due to a new method of completing aircraft preflight inspections following flight instead of just prior to flight. This technique significantly improved the rate of aircraft able to meet the flying schedule, and the first eight-plane formation of B-29s was launched on 22 October. Finally, when the 504th, 505th, and 6th Bomb Groups' ground echelons prepared to deploy overseas in advance of their air and flight echelons, the 315th's ground echelons easily assumed their duties to facilitate their departure. Thus, the unit overlap accelerated the training of 315th personnel and prepared them to provide operational support to the departing groups' air and flight echelons.

On the other hand, the unit overlap severely strained the limited resources at the Nebraska bases. Office, transportation, mess hall, post exchange, and housing facilities designed to handle one bomb group had to stretch to meet the needs of two. Consequently, overcrowding was commonplace. The housing shortage was particularly critical with little relief provided by the small communities surrounding the bases. Pyramidal tents sprang up at each base to provide temporary housing for the men of the 16th, 501st, and 502nd Bomb Groups. For the 502st at Harvard Field, the area where the six-man pyramidal tents were set up was promptly nicknamed 'Tent City." As more and more tents sprang up, the men began to make improvements to their new housing area, and Tent City developed a character all its own.

The 'naming' of their tents became somewhat of a major christening what with all the tent-dwellers openly contesting with their neighbors with newly painted signs ranging from 'Commanding General' to 'Esquire Club'; 'Club Rendezvous';... and other similar names. Each tent group tried its best to install new innovations varying from painted interior and exterior woodwork to new electrical installations. Anything to outdo his next-door neighbors' tent for originality became the vogue.

The problems of overcrowding continued until the 504th, 505th, and 6th Bomb Groups deployed overseas.

Actions to maintain and improve morale in the 315th continued throughout the training period. Unit special services sections provided day rooms equipped with pool tables, ping pong tables, radios, magazines, books, writing materials, card tables, and coke machines. Sports leagues were started in softball, volleyball, basketball, and bowling. Movies were shown weekly at most units. Newspapers were started by some units like the 331st Bomb Group-still based at Dalhart-which first printed The Target on 25 August. Dances were held regularly, and on holidays, with local girls, nurses, and USO girls invited to attend.

Fenolli hoppers from Brooklyn, toddlers from Massachusetts, hop-cats, clucks, and jitter-bugs from everywhere jammed the floor to the Base Gym in wicked rug cutting last eve to make the initial dance of the 331st Bomb Group a success. There was plenty of food for wolfish GIs and partners, and drinks (soft) too. But what pleased the EMs most were the Dalhart fluffs and WACs who braved mud and rain to make the evening memorable. During intermission, Tick' Jones brought down the house with his tap-dancing. Miss Mary L. Barnes, hostess at the Colored Service Club, charmed the audience with sweet singing, while SSgt Joseph P. Griffin moved them with Ink Spots. The men of the 331st look forward to future dances of which there will be many.

There were also special events such as the 16th Bomb Group's trip on 7 October to Lincoln, Nebraska, to attend the football game between the Second Air Force "Superbombers" and the Iowa Naval Preflight School. Finally, offbase activities such as the local USO, Veterans of Foreign Wars Clubs, theaters, shopping facilities, dance halls, and high school sports events complemented on-base activities to support morale.

A singularly important morale factor in the 315h Wing was the personal pride in being a member of a B-29 Superfortress outfit. The Army Air Force and the news media had repeatedly heralded the final development of the new, powerful B-29 and associated very heavy bomber units. The men of the 315th knew they were part of a Superfortress outfit, a new, elite flying organization. This knowledge gave each man an inner pride and sense of importance in the war effort.

Routine unit activities and a tragic event characterized 315th operations in October. The 331st and 501st Bomb Groups held their second bivouac training exercises. The 331st also sent an advanced ground echelon to McCook AAF, McCook, Nebraska, to prepare for its upcoming move there in November. Colonel Kenneth 0. Sanborn assumed command of the 502nd Bomb Group on 6 October. Major George Harrington and Captain Nathaniel Grimm, from the 315th Headquarters staff, visited the 501st at Harvard Field to assist that unit in winterizing some 185 tents in Tent City. Clothing shakedowns were held in each unit to determine needs for the coming winter months. Medical and dental examinations continued at a hectic pace as new personnel joined their units. Halloween dances were held at the end of the month to maintain morale. Unfortunately, the month's positive gains were somewhat marred by the loss of Captain Edward M. Woddrop, Assistant Operations Officer of the 17th Bomb Squadron, who was killed in an aircraft ground mishap at Fort Worth, Texas, on 11 October.

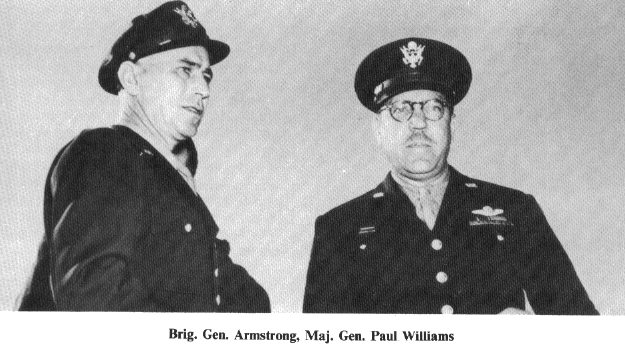

In November, a combat veteran named Brigadier General Frank A. Armstrong was selected to command the 315th Bomb Wing. He had served as a combat group and wing commander in Europe until August 1943. During his assignment as Commander of the 97th Bomb Group, Gen Armstrong earned a reputation as a tough and demanding officer. Major Paul W. Tibbets, appointed by Gen Armstrong to be the 97th's Executive Officer, witnessed Gen Armstrong's leadership style.

As a commander, Frank Armstrong was a leader not a 'driver,' but he demanded compliance and performance. He knew what had to be done; how to do it; and made it abundantly clear what he expected of everyone. Frank was not afraid of responsibility and when warranted he took the blame for mistakes rather than remain silent and let subordinates take the brunt. Frank never asked anyone to do any thing he himself would not do....Frank Armstrong was a mans man and looked up to by those working with him to attain the objectives but feared by those who shirked their duty.

Gen Armstrong* left the 97th to command the 306th Bomb Group and promptly turned that troubled unit into an effective combat force. After his return to the United States, Gen Armstrong joined the Second Air Force and subsequently commanded both the 46th Bombardment Training Wing, Ardmore, Oklahoma, and the 17th Bombardment Training Wing, Grand Island AAF, Nebraska. Gen Armstrong departed the latter assignment to command the 315th.

*The fictional character Frank Savage in the popular movie Twelve 0'Clock High was based on the real-life experiences of General Armstrong in the European theater.

On 18 November 1944, Gen Armstrong assumed command of the 315th Bomb Wing (VH). He promptly held a briefing and outlined his command philosophy to his wing staff and group commanders.

I don't contemplate any wrangling between the Group Commanders, their staff, or the 315th staff. We are from this day on, one big family. I hope it will be a happy family. We have only one purpose in mind, and that is to train the four Groups of the 315th, and needless to say I don't have to elaborate on training, because when the 315th goes out I expect and demand that it go out the best trained Wing in the B-29 program... I expect to have the best damned Wing that ever goes out of the country, and I expect to bring it back. What more can I tell you?

Gen Armstrong's commitment and reputation as an effective combat commander fueled a sense of purpose and cohesiveness throughout the 315th.

November 1944 was a month of consolidation and planning for the 315th. The 331st Bomb Group moved to McCook AAF on 11 and 21 November to complete the transfer of all 315th bomb groups to their pre deployment training bases in Nebraska. Of course, the 331st experienced the same unit overlap situation as its sister bomb groups had earlier. Meanwhile, the 501st took sole control of Harvard Field and promptly moved the men from Tent City to permanent barracks. Sixty-two flight crews were assigned to the 315th following their completion of B-29 training at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Each of the bomb groups received 15 or 16 of the new flight crews as the initial allotment toward their authorized strength of 50 crews. The 315th Wing Headquarters also initiated tentative planning for the wing to conduct simulated combat training flights in the Caribbean. By the end of the month, the bomb groups were finalizing training plans to start flying operations in December.

The 315th enthusiastically supported two American traditions in November. The 6th War Bond Drive was in full swing throughout the month, and personnel had the opportunity to contribute on payday. At the 501st, one NCO in each barracks was designated as War Bond representative to encourage purchases. Officers in the 501st were also encouraged to purchase "at least one $18.75 bond over and above allotments." On 30 November, each unit held its own Thanksgiving celebration, and the men and their families gathered together in the mess halls for turkey dinners with all the trimmings. Entertainment was also provided throughout the day. At the 502nd, Frankie Masters and his band played in one of the hangars during the afternoon and later in the evening for the officers' dance. The War Bond drive and the Thanksgiving Day celebrations were highly successful.

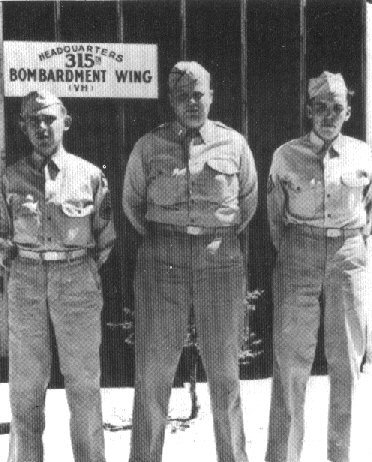

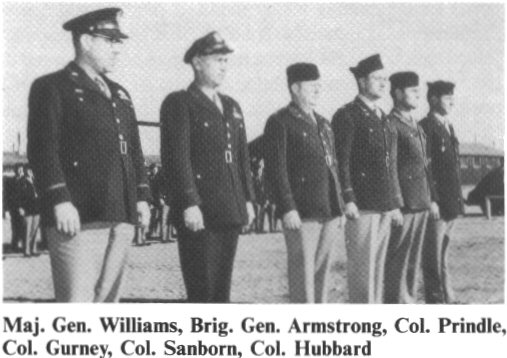

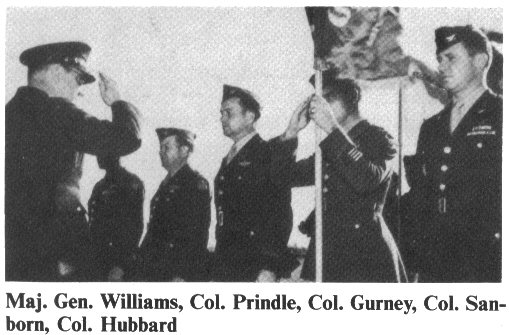

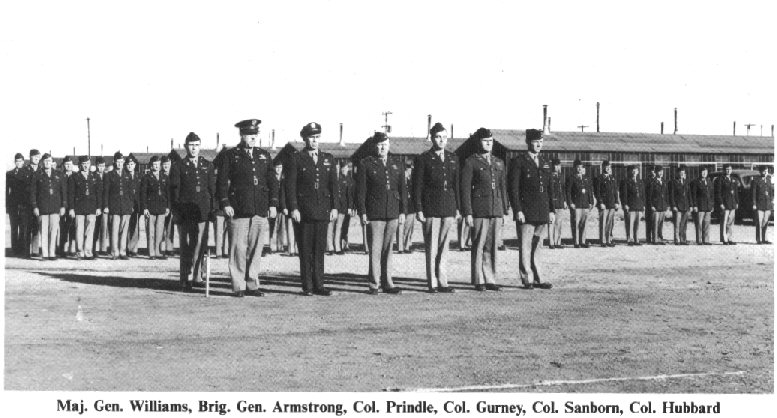

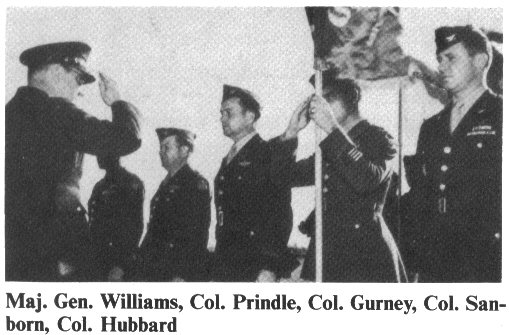

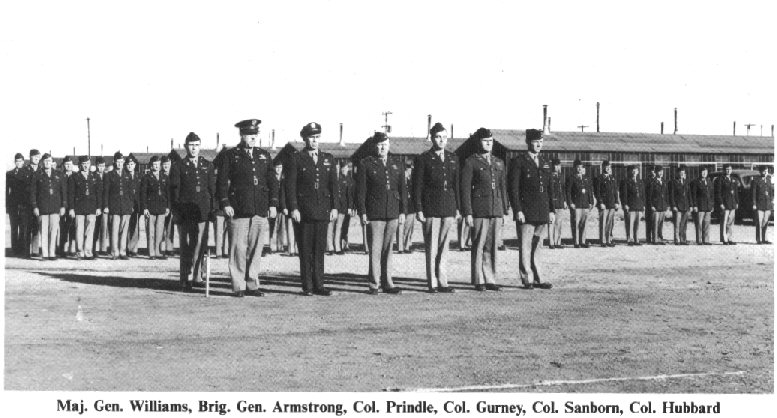

On 7 December, the 315th Wing and its four bomb groups received their colors and standards. Major General Robert B. Williams, the Commanding General of Second Air Force, made the presentations at a ceremony held at Peterson Field, Colorado. Gen Frank Armstrong received the colors for the wing while Colonels Hoyt Prindle, Samuel Gurney, Kenneth Sanborn, and Boyd Hubbard accepted the colors for the 16th, 331st, 501st, and 502nd Bomb Groups, respectively. This ceremony, held on the third anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, symbolically marked the beginning of the 315th Wing as a distinct combat entity.

Bomb group flight operations began in December. Aircrew ground and flight training schedules were completed and published. The flight crews who had arrived in November were assigned to one of three squadrons in each Bomb group. Each squadron was divided into three flights and while one flew, the other two completed ground training. As specified for the first phase, initial flight training for the B-29 crews was limited to local transition missions. These included routine takeoffs and landings, short cross-country lights, and emergency procedures practice. The flight training was also completed in the B-17 aircraft still assigned to the bomb groups pending delivery of additional B-29s. Unfortunately, the month's flight training was hampered by the severe Nebraska winter.

The 315th Wing Headquarters flight personnel also began B-29 flight training in December. They had been unable to fly until December because no B-29s were available to the wing headquarters at Peterson Field. However, on 18 December, the Second Air Force assigned the newly activated 509th Composite Group to the 315th. Subsequently, the 315th borrowed a B-29 from the 509th, and the wing's flight personnel immediately began transition flying to parallel the bomb groups' flight training activity.

The assignment of the 509th Composite Group to the 315th raised many questions. The 509th was based at Wendover Army Air Field, Utah, and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets, Gen Armstrong's former Executive Officer at the 97th in Europe. The 315th became the 509th's parent unit due to a request by Lt Col Tibbets.

At the time of my assignment to organize and train a unit capable of delivering atomic weapons, I was assigned to a B-29 instructor training school at Grand Island, Nebraska. Frank Armstrong was the [17th Bombardment Training Wing] Commanding General. This was September 1944. When Frank got the 315th Wing, I asked Second Air Force to assign the 509th to his Wing for the obvious reasons, i.e., our past relationships and the fact that the 509th, once outside the U.S., would have to be attached to some organization.

Although the 509th became part of Gen Armstrong's command structure, he did not know the highly secret mission the 509th was training to accomplish. The guarded secrecy also prevented Gen Armstrong and his staff from discovering the 509th's mission or interfering with its operations. As a result, the 315th wing staff wondered what affect the 509th would have on the wing's overseas deployment date and future combat operations.

A special project known as the "Gypsy Task Force" was inaugurated in December and affected the 315th's future training operations. In the late fall of 1944, the Second Air Force was concerned about the dramatic decline in flying training time logged at the VHB bases in Nebraska and Kansas due to adverse weather. In response to this situation, Colonel William A. Miller, Commanding Officer of Grand Island AAF, proposed setting up training bases in the Caribbean area to train VHB flight crews. In December, Second Air Force permitted Col Miller to conduct a two week test of the idea at Borinquen Field, Puerto Rico, using the 6th Bomb Group (VH) as the test group. The 6th Bomb Group quickly proved the practicality of the operation by completing all training requirements ahead of schedule. Consequently, Second Air Force promptly approved Col Miller's plan and christened the new operation as the Gypsy Task Force. The plan called for the establishment of three bases at Antilles Air Command fields in the Caribbean: Vernam, Jamaica; Batista, Cuba; and Borinquen, Puerto Rico. These fields became the advanced flying training bases for all VHB units preparing to deploy overseas.

The 502nd Bomb Group was the first 315th unit to participate in the Gypsy Task Force. Since the 6th Bomb Group had completed all training ahead of schedule, the 502nd Bomb Group, collocated with the 6th at Grand Island, was sent to Borinquen Field and began flight operations on 22 December. Under Project Gypsy, all B-29 bomb groups were scheduled to train in the Caribbean in the early months of 1945 using the personnel rotation system established by Second Air Force.

With necessary exception, 1/3 of the combat crews of each VH group will accomplish flying training with the Gypsy Task Force for ten (10) days; 1/3 of the combat crews will be involved in the movement either to or from the advanced area and understudying the crews in training; the remaining 1/3 of the combat crews will accomplish ground school and flying training at their home stations in the rear area.

Thus, the Gypsy Task Force project provided an excellent opportunity for the 315th's bomb groups to escape the wintry conditions in Nebraska and to complete their flight training.

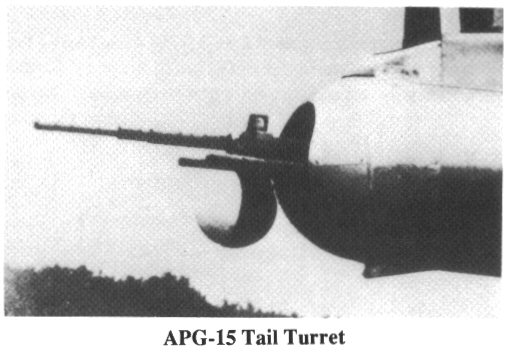

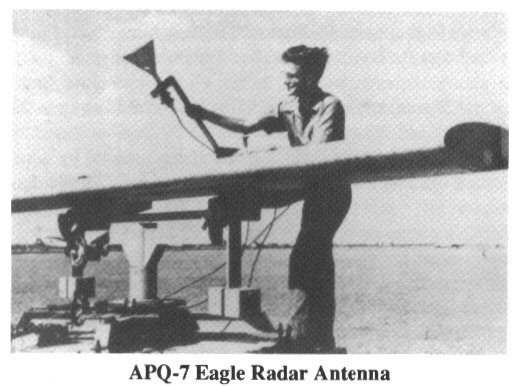

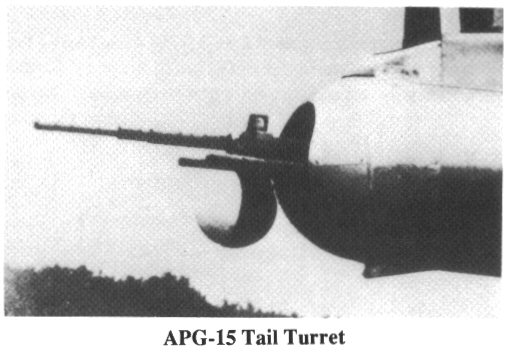

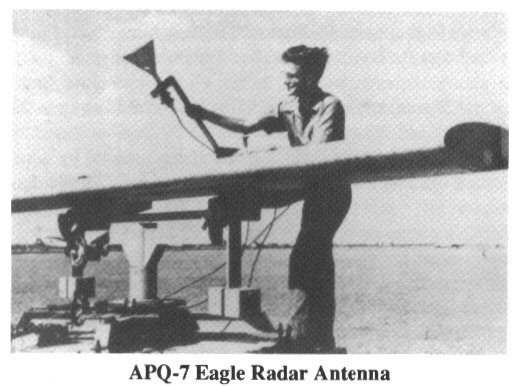

On 17 December, the 315th Headquarters received an important teletypewriter message (TWX). The TWX directed special modifications to the wing's B-29s, including the removal of the armament and central fire-control system. Instead, the B -29s were to be equipped with only a new radar-directed tail turret, the APG-15, having three 50-caliber machine guns. The Plexiglas gunners' blisters protruding from the sides of the B-29 were also to be removed and replaced with smooth enclosures. The 315th flight crews were reduced from 11 to 10 men by replacing the 3 original gunners with 2 visual scanner positions. The TWX also notified the 315th that the APQ-13 radar navigation and bombing system would be replaced by the new AN/APQ-7 radar, code named "Eagle." This TWX raised many questions about the future role of the unit.

The modifications to the 315th's B-29s were based on a special study conducted at Alamogordo, New Mexico. The study originated to test the vulnerability of the B-29 to fighter attack. Lt Col Paul Tibbets, while assigned to Grand Island AAF, had been ordered to test the B-29 in simulated combat with fighters at Alamogordo AAF, New Mexico. Unfortunately, the heavyweight B-29 proved difficult to control at 30.000 feet. Lt. Col Tibbets reported, "A too-steep bank or sudden movement of the controls might cause the plane to stall." Then one day his test B-29 was down for repairs at Grand Island, and he borrowed another B-29, equipped only with tail guns, and took off for Alamogordo. The lighter weight B-29's climb performance was remarkably better. In subsequent tests above 30,000 feet, Lt. Col Tibbets found that he "could turn in a shorter radius than the attacking P-47." Further tests showed the lightweight B-29 could also fly well above 30,000 feet and at speeds greater than some fighters were capable. Based on the Alamogordo study, the 315th was selected as the first unit to test the tactical potential of lightweight (stripped) B-29s in combat against Japan. The stripped B-29s would also be able to carry the maximum 20,000-pound bomb loads over the long distances required to reach Japan from current American bases in the Pacific. With the addition of the new APQ-7 Eagle radar, the stripped B-29s would also be able to conduct precision bombing from higher altitudes and in adverse weather. Thus, the 315th's new combat role became high-altitude, all-weather, precision bombing. As a result, the 315th was directed to strip its B-29s until modified B-29s, designated B-29Bs, could be rolled off the assembly line.

On 20 December, the 315th received its warning order for movement to the Pacific Theater of Operation (PTO). The warning order established readiness dates of 1 February and 1 April for the ground and air echelons, respectively, of the 315th Headquarters, 16th Bomb Group, and 501st Bomb Group. These units immediately began preliminary preparations for the movement Later, Air Terminal service Command personnel arrived to give three days of instruction on proper methods of packing and crating supplies and equipment The units then began the difficult task of building crates and boxes for shipping equipment overseas. The apprehension caused by the preliminary actions was heightened by the receipt of the movement order on 26 December. Fortunately, the concurrent announcement of numerous promotions and a new furlough policy helped to offset the apprehension. The furlough policy entitled personnel to 15 days of leave prior to their departure date unless they had already used 15 days since 1 July. Nonetheless, everyone knew the 315th would soon move out for overseas duty.

Despite the hectic pace in December, the Christmas spirit was alive in the 315th. At the 411th Bomb Squadron, the mess hall was decorated in style with trees, wreaths, streamers, and giant candles. At the 16th Bomb Squadron, the Jewish men volunteered to perform mess hall duties on Christmas. Col Gurney, the 16th Bomb Group Commander, commended their actions by stating, "When men work together this closely, with mutual regard for each other's religious beliefs, no foe, however strong, can ever break the spirit of American idealism." Tragically, this was the last Christmas for some men as the 315th prepared for combat in 1945.

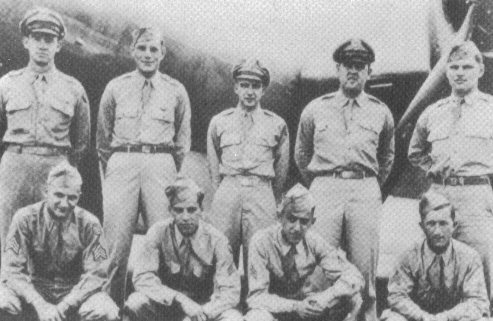

Bob Hope, Brig. Gen. Armstrong, Frances Langford

Brig. Gen. Armstrong, Col. Tifton, Bob Hope

The year 1944 closed on a somber note for the men of the 430th Bomb Squadron, 502nd Bomb Group. On 31 December, one of the squadron's B-29s crashed during a training flight at Borinquen Field. Captain Frank H. Beales, pilot, and First Lieutenant Barclay H. Beeby, instructor pilot, had tried to immediately return to the airfield to land their B-29 following the failure of the number one engine on takeoff. However, the aircraft rolled over and crashed just 500 yards from the end of the runway. Five of the six-man crew on board were killed. This was the first aircraft accident for the 315th at the Gypsy Task Force, and it wouldn't be the last.

In January 1945, Second Air Force produced a new training manual for the 315th. The flight manual was entitled, B-29 Flight Training Directive (Special) and outlined the revised training requirements for the 315th's high altitude, precision instrument bombing mission. It deleted the requirement for formation flight training and increased the number of long-range missions. Fortunately, the 315th's planned operations in the Caribbean under the Gypsy Task Force were ideal for completing the new training requirements.

The 16th and 502nd Bomb Groups began rotating personnel to the Caribbean in January. They were assigned to Gypsy Sub Task Force No. 3 at Borinquen Field, Puerto Rico.

The first [16th] aircraft for Borinquen Field left Fairmont Army Air Field on 3 January 1945. On board were Lieutenant Colonel Andre F. Castellotti, Deputy Group Commander and Tactical Inspector, Major John S. Gillespie, Assistant Group Operations Officer, and Captain Oliver C. Mosman, Jr., Group S-2. Together with other officers, they constituted the advance party, which was to prepare the way for the rest of the organization. The B-17 made the trip in less than 16 hours with one stop at Miami, Florida, for refueling. It was followed on 5 January by more B-l7s and on 9 January, the first B-29s arrived with crews ready for training. The 15th Squadron was the first to send its crews to Puerto Rico. It was to be followed by the other two squadrons in order.

This personnel rotation scene was repeated many times by the 315th bomb groups in early 1945 to complete the advanced phase of flying training. The flight crews flew numerous 3,000-mile overwater missions under weather, sea, and terrain conditions similar to those they would face in combat. Additionally, the flight crews and ground support personnel worked to improve operational efficiency since this was their final simulated combat training opportunity before they deployed. Naturally, this division of unit operations between the Caribbean and Nebraska created difficult supply, administrative, maintenance and personnel problems. However, they were handled, and the ideal training conditions more than compensated for the logistical problems encountered.

To support the groups' divided operations, maintenance personnel spent many long hours exposed to Nebraska's winter weather trying to keep the B-29s flying. The B-29 was particularly troublesome for maintenance because its engines ran too hot and failures were common. Its cylinder baffles were inadequate and contributed to engine overheating. In addition, Boeing's design of the landing gear door and bomb-bay door systems led to engine over heating.

The landing gear doors were operated by an electric jackscrew and didn't come up until the gear was up. The bomb bay doors were also operated by jackscrews. Both of these systems took much too long to complete their cycle. On takeoff the engines would overheat just waiting for the gear doors to get closed. The added drag only made the engine overheat problem more severe.

Leaky carburetors caused frequent engine fires until maintenance personnel discovered the problem was due to the carburetor mounting bolts bottoming out before they were snug enough to seal the carburetor. The cold weather in Nebraska magnified these problems because most of the maintenance had to be performed outside due to limited hangar space. At Fairmont AAF there were only three hangars, and each hangar accommodated only one B-29. Moreover, the B-29's engines were also difficult to start in cold temperatures and required special priming by maintenance personnel to get them started. Since the groups' maintenance staffs were split between the Caribbean and Nebraska bases, some men worked two and sometimes three shifts without sleep on the cold Nebraska flight lines trying to keep the Superforts operational.

During January, the 315th increased its preparations for deployment and operations overseas. Between 3 and 6 January, the 315th Wing Headquarters successfully conducted a Command Post Exercise simulating jurisdiction over all four bomb groups in the combat theater of operation. From 11 to 30 January, Gen Armstrong and his selected staff traveled to the Marianas to study the 315th's future home for combat operations. Ground echelons of the 16th and 501st Bomb Groups completed their final preparation for overseas movement (POM) processing. The 501st also completed its final bivouac training exercise before deployment. On 24 January, the 331st Bomb Group received its movement orders as well as a new Group Commander, Colonel James N. Peyton. Moreover, the 331st was at full strength for the first time since activation with the arrival of its final personnel elements from Dalhart Field and 31 additional flight crews. The Second Air Force also increased each group's authorized aircraft strength from 30 to 45 Superforts. Finally, by the end of January, all in-unit B-29 modifications were nearly complete, except for the installation of the APQ-7 radar which was unavailable.

The 315th Wing Headquarters submitted a special request to Second Air Force for civilian experts in the B-29. By January, it was increasingly apparent that the VHB units in training were not being kept abreast of the B-29 equipment improvements made at the factories. Consequently, the 315th wanted 24 civilians to accompany the wing overseas, if necessary, to bring the wing's specialist up to date on the latest B-29 systems improvements.

Among others, the following type experts were listed in the request: a man from the Wright Aeronautical Works to operate on engines; a Boeing trained engineer; an advisor on flight controls from the Minneapolis Honeywell Corporation; a Goodyear fuel cell repairman; a Western Electric radar worker; a bombsight maintenance man from the Victor Adding Machine Company and others. If this request is granted, these civilians would be allotted to the Wing and groups according to their respective specialties and the needs for their services.

This request reflected Gen Armstrong's demand to have highly qualified unit personnel and the best trained B-29 wing.

In January, the Bob Hope show toured several of the 315th's units. Between 1630 and 1800 hours on 11 January, Bob Hope, Jerry Colona, Frances Langford, Vera Vague, and Tony Romano performed for the enlisted men of the 315th Headquarters at Peterson Field. Later that night at the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs, these entertainers were the honored guests at a reception dinner for Gen Armstrong and officers of the 315th Wing. The next day, the Bob Hope show was repeated for the members of the 331st Bomb Group at McCook Army Air Field. Entertainment by Hollywood stars was a significant morale booster for the 315th as well as other units throughout the war.

The Gypsy Task Force was costly for the 502nd Bomb Group in January with four training accidents, two resulting in fatalities. In the first accident, a B -29 assigned to the 411th Bomb Squadron ditched off the coast of Haiti due to an uncontrollable fire in the number two engine. The plane broke in half during the ditching, and only five men from Crew 1104 were rescued the following day. The other five crew members were never found. Later, on 26 January, Crew 1107 from the 411th crashed near Fort Riley, Kansas, while enroute from the Caribbean to Grand Island AAF. The accident was due to fuel exhaustion brought on by excessive fuel consumption while flying in strong headwinds. Six of the 15 men on the B-29 were killed. On the same day. Crew 1117, 411th Squadron, crash landed near Lexington, Missouri, while flying to home base. Again the cause of the accident was fuel exhaustion due to adverse weather and navigational error. Fortunately, there were no casualties.

The final accident for the month occurred on 27 January. Crew 203 from the 402nd Squadron was on a practice bombing mission out of Borinquen Field when the number one and number two engines and electrical system malfunctioned. The crew had to shut down the number two engine while the number one engine had to be operated at drastically reduced power. After checking the electrical problem, the crew found they could not extend the landing gear or wing flaps. The young aircraft commander, Captain Arthur W. Dippel, and his crew headed for Borinquen Field, losing altitude all the way. Once over land and at 4,000 feet, Capt Dippel rang the alarm bell for his crew to bail out. Four men in the front compartment bailed out, but those in the rear of the plane did not hear the bell. By the time he discovered this, Capt Dippel knew the aircraft was too low for the remaining crew to bail out An instructor pilot was in the copilot's seat and began flying the airplane toward the runway at Borinquen Field. On the final approach, Capt Dippel took over the controls and made a perfect no-gear, no-flaps crash landing. As the aircraft skidded along the runway on its belly, sparks caused the plane to catch fire before it came to a stop. Fortunately, all the men escaped before the ensuing fire spread through the aircraft. The month of January was costly in lives and aircraft for the 502nd Group, but it could have been worse.

Seated Foreground: Jerry Cologna, Ellen Drew, Lt.C. Sy Bartlett, Col. Ken Sanborn

Maj. Brown, Lt.C. George Harrington, Rosemary Harrington, Col. Emile Kennedy, Mrs. Brown, Col. Hoyt Prindle, Mrs. Bright, Capt. Wayne Bright

In February, the 315th units were busy completing their final preparations for overseas movement (POM) actions. Ground echelons of the 16th and 501st Bomb Groups completed POM processing and packed and crated their equipment for shipment overseas. In a three-week period, the 501st crated and stacked more than 175,000 pounds of equipment in plywood cases and marked each case with the unit code number, box number, and coded destination. On 20 February, advance parties from the 16th and 501st went to the Port of Embarkation (POE) in Seattle to coordinate final preparations for unit deployment. Meanwhile, the 331st and 502nd Bomb Groups secured and packed athletic and recreational equipment since these items were difficult to get overseas.

During the month of February, much of the Special Service department's activity revolved about morale problems in preparation for overseas movement. Among the pieces of recreational equipment which arrived during the month and were packed and prepared for shipment were: a public address system, a 2,200 book library, an ice-making machine capable of eighty pounds per hour, washing machines, electric irons, coke machines, bar fixtures, photographic equipment for a photo club, beer coolers, and a great amount of athletic equipment. Individual Group members examined much of the material secured and responded favorably.

The 331st and 502nd followed in the footsteps of the 16th and 501st which were scheduled to deploy first. All four bomb group ground echelons were poised and ready for movement overseas by the end of the month.

By February 1945, all 315th personnel had completed, or were scheduled to complete, their final phases of pre deployment training. Second Air Force directed the 315th Headquarters staff to participate in Project Gypsy prior to deployment overseas, to increase wing staff and group coordination in unit combat operations training. An advance party from the 501st bomb Group went to Vemam Field, Jamaica, to prepare for its scheduled Gypsy Task Force training. On 16 February, the first 45 of the scheduled 180 wing and group officers began a 2 1/2-week training class on the APQ-7 Eagle radar at Victorville, California. The 315th Wing Headquarters also formulated plans to send crew radar operators to Boca Raton, Florida, and Victorville, California, for extensive training in the APQ-7 radar. Moreover, the 315th Wing Radar Intelligence Section began a program to secure radar identification charts and scope photos of Japan for bomb group and squadron study.

Photo strike pictures of B-29s from the XXI Bomber Command were received and distributed to the Groups for an exercise involving interpretation and compliance with the Wing photo interpretation report system. A program consisting of three problems for radar and visual target and terrain identification was distributed to the Groups, placing emphasis on the industrial targets of Japan.

Finally, the 315th was granted authorization to obtain 24 civilian technicians to supplement the training of its maintenance specialists. By the end of February, time for training was rapidly running out.

In March, the 331st and 501st Bomb Groups began training in the Caribbean. They were assigned to Gypsy Sub Task Force No. 2 at Vernam Field, Jamaica, which became operational with the arrival of the 501st on 3 March. Originally, training for the 331st and 501st was scheduled for February, but was delayed until March because the facilities at Vernam were poor and the runway was too short for B-29 operations. After arriving at Vernam, the 331st and 501st faced a severe shortage of maintenance personnel and maintenance equipment, especially aircraft and radar parts. In addition, no night operations were permitted because of unlighted terrain obstructions around the field. Despite these problems, the 331st and 501st put their best efforts into accomplishing the training.

The day was divided into two flying periods of six hours each. Briefing was held at 0300 each morning and at 1000 for the training missions involving bombing and gunnery. Two adequate bombing ranges, Walker Bay and Portland Rock, were situated within a fifty mile radius of the base, and, since our ranges in Nebraska had serious limitations, especially for radar bombing, every effort was made to accomplish all radar bombing requirements from Vernam and these efforts were successful. The base's situation also afforded a good aerial gunnery firing range over the ocean and three P-63* type fighters were based at Vernam to provide mock interceptions for camera gunnery. Once our operations began to function smoothly, a good amount of training was accomplished.

[*The P-63 Kingcobra was a modified version of the P-39 Airacobra.]

Flight training included long-range, 13-hour missions to the eastern coast of the United States and back before nightfall at Vernam Field. The simulated combat operations for the 331st and 501st at Vemam were challenging and productive with all personnel honing their respective skills.

On one mission, First Lieutenant Leonard Jones, 501st Bomb Group, and his crew tested the theory of the stripped B-29 versus fighters at high altitude. The crew took off, climbed to 25,000 feet, and radioed down to send a P-39 fighter up. They knew the P-39 had been designed with high-pitched wings for maneuverability, and they believed it wouldn't be able to reach the B-29s at altitude. Within minutes the P-39 was right off Lt. Jones' wing tip. He climbed to 30,000 feet, but right away the P-39 was there again. After this experiment, Lt Jones* crew was convinced they would see Japanese fighters at 30,000 feet when they started combat operations overseas. Until then, they wanted to enjoy then- stay in the Caribbean.

The Caribbean environment was great for morale. The warm, tropical climate at Borinquen and Vemam Fields was a welcome change of pace from the wintry days in Nebraska.

It just couldn't happen to us. But it did! Uncle Sam actually paid our expenses for a trip to the land of 'Rum and Coca-Cola', and he picked the best time of the year for it, January, February, and March. The War Department called us The Gypsy Task Force' and they meant it. Borinquen Field, Puerto Rico, was the ideal spot for a Gypsy. Swimming pools, a golf course, and soft, tropical breezes that were afar cry from the sub-zero blasts that were hitting FFAF (Fairmont AAF).

At Vernam Field, Col Peyton, the 331st Group Commander, also set up a pass system for 20 officers and enlisted men each day to take the 2-hour train ride to visit Kingston. Unfortunately, the morale building experiences at the Gypsy Task Force were sometimes offset by tragic training accidents.

Two more fatal aircraft accidents occurred in March. In the first on 6 March, a B-29 assigned to the 402nd Bomb Squadron, 502nd Bomb Group, crashed into the golf course near the runway at Borinquen. Earlier in the flight, the plane was at 10,000 feet and the number one and number three engine propellers malfunctioned. By the time the pilot, Second Lieutenant Harold C. Anderson, and his crew returned to Borinquen, the number three engine had been feathered and the number one engine was on fire. The aircraft stalled while trying to land and crashed short of the runway. Six of the nine crew members on board were killed. On 10 March, the 501st Bomb Group had its first fatalities. A B-29, piloted by First Lieutenant V. Tulla, crashed while trying to land at Alexandria AAF, Louisiana. The ten-man crew was killed. It was a severe blow to their fellow group members, but the intensive training continued.

In March, 315th personnel finally started learning about the APQ-7 Eagle radar. The Eagle radar had been conceived by professor Luis W. Alvarez, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and developed by MIT's radiation laboratory and Bell Telephone Laboratories. The new Eagle radar equipment employed a much higher frequency than previous radars and gave a clearer presentation of ground images on the radarscope. The Eagle was ten times more efficient than the radar equipment being used in other B-29s.

The antenna was the key to the APQ-7 radar bombing system. The antenna was a straight structural beam 16 feet long, mounted on the lower part of the fuselage. It mounted 250 dipoles and used electronic scan rather than rotational scan. It produced a much finer degree of resolution, but it surveyed only a 60 degree forward sector. It had a .4 degree beam width.

The antenna was housed in an 18-foot wide, airfoil-shaped section and mounted perpendicularly on the underside of the fuselage. The mounting of the antenna below the fuselage permitted greater target identification but also made the B-29 look somewhat like a biplane. The APQ-7 Eagle radar was a new and significant element in the 315th's future combat operations.

To use the Eagle radar system, the 315th's crews had to learn a new method of attack called synchronous radar bombing. With the APQ-7 system installed, the radar bombardier and his radarscope were not collocated with the Norden optical bombsight in the nose of the B-29. Instead, the radar bombardier sat aft in the navigator's compartment and his radar was synchronized electrically with the optical bombsight. During a bomb run, the radar bombardier tracked and aligned the target using a reticle on his scope. This radar information was automatically fed to the bomb sight and produced a radarscope display of the target track to fly, ground speed, and time for bomb release. Thus, the term synchronous radar bombing meant the bombsight was used in conjunction with the radar equipment during the bombing attack.

The 315th's flight crews modified their bomb run procedures to incorporate the synchronous radar bombing method. The target information displayed at the optical bombsight was also presented on an indicator in the cockpit.

The pilot set the plane on automatic pilot, turned to the track displayed on the PDI (Pilot1 s Direction Indicator), and held that course to the target. He also stabilized the airplane speed and altitude, so that the pilot himself was controlling all three parameters of the bomb run. In the usual approach to optical bombing, the pilot only controlled speed and altitude; the bombardier held the course.

During the target run, the radar bombardier used the APQ-7 radar and visual sighting to spot the target while the autopilot's gyroscopes kept the aircraft straight and level. At the target, the bombsight indicators came together, a red light flashed in the cockpit to signal the bomb-bay doors had snapped open, and the bombs were released. The crews spent many hours learning the synchronous radar bombing method and even more hours in the air trying to perfect their procedures.

In March, the 501st Bomb Group picked up the first of the 315th's "Flyaway" B-29Bs at the Bell-Marietta aircraft factory in Georgia. The term flyaway meant the flight crews picked the aircraft up at the factory and flew it to their home bases prior to deployment overseas.

The crews that received them have certainly 'gone to town.' The first plane, #600, was given to Major Tintensor, of the 21st Squadron, who immediately named it 'ROADAPPLE' with a picture of a horse painted on the side of the nose. The second ship, #615, was given to Captain Braun, also of the 21st Squadron, who immediately named his airplane 'BEEGAZBURD,' which was very appropriate for the occasion.

The B-29Bs were specially modified B-29s with the armament removed and the APG-15 radar tail gun turret and APQ-7 radar installed. In addition, the landing-gear doors and bomb-bay doors had been modified to a pneumatic system to reduce system cycling times. The engine baffles were also modified to make the engines run cooler. The flyaways represented the bulk of the aircraft programmed for the 315th to use in combat against Japan. Thus, the four bomb groups continued to pick up additional flyaway B-29Bs as they came off the assembly lines.

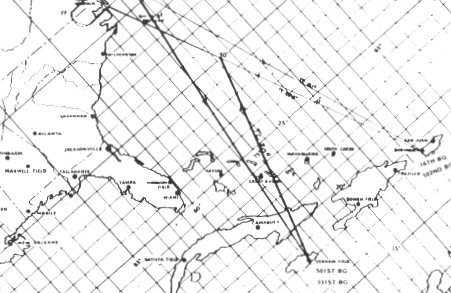

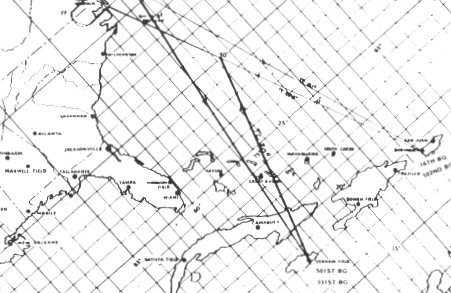

The 315th flew its first coordinated wing training mission in the Caribbean on 27 March. A maximum bomb load, 3,000-mile mission was planned from Borinquen Field to Charleston, South Carolina, closely simulating a Pacific theater combat mission from the Marianas to the Yokosuka Naval Base near Tokyo. The Gypsy Task Force (GTF) Headquarters acted as a bomber command and authorized the 315th Wing staff to act as the tactical headquarters. The GTF sent a field order to the wing directing it to attack Yokosuka, and the 315th's Operations and Training staff then issued a wing field order to alert the bomb groups. Each group briefed its crews on the mission, including a detailed description of enemy defenses in the target area. The wing launched 16 aircraft for the mission using 15-minute takeoff intervals. Two 502nd Bomb Group crews had engine trouble over the target area and made emergency landings at Jacksonville and Morrison Fields in Florida. The remaining aircraft successfully dropped their concrete bombs in the ocean near their simulated target and returned to Borinquen.

The 315th's simulated attack on Yokosuka (Charleston) was a valuable training exercise. For the first time, the wing and group staffs acted as a tactical organization and used operational procedures similar to those in combat. Their coordination on mission planning, briefings, reports, communications, and maintenance improved the cooperation between the staffs. On the other hand, the mission revealed flight crew weaknesses in radar identification, radar bomb run training, and LORAN navigation procedures. As expected, the crew members who had attended the APQ-7 school at Victorville were better at radar target identification than those who had not yet attended. The results of this mission indicated the 315th needed to fly additional training strikes using the Eagle radar equipment and procedures it would employ in combat against the Japanese industrial targets.

A second wing mission was immediately planned for 6 April. A wing conference was held at Borinquen Field on 4 April to plan the mission. The Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company at Norfolk, Virginia, was the target, simulating the Mitsubishi Drydock Company at Kobe, Japan. Once again, the GTF acted as bomber command and ordered the wing to attack the target with all four bomb groups. The wing staff alerted the groups, and representatives from the 331st and 501st flew to Borinquen from Vemam and joined the 16th and 502nd for the wing briefing held on 5 April. The bombing attack was planned for 30,000 feet using a wind vector, or no drift, downwind bomb course similar to the first mission. After the briefing, the 331st and 501st men returned to Vemam to brief their crews and prepare for the mission.

The following morning, 6 April, the 315th launched nine B-29s to strike the Mitsubishi (Newport) installations. The 16th and 502nd supplied five aircraft from Borinquen Field while the 331st and 501st launched four planes from Vemam Field. The weather over the target was a solid overcast at 22,000 feet and ideal for radar bombing. Unfortunately, the two 502nd crews had to make a dead reckoning bomb run, but all other crews used radar bombing and had excellent results. The second wing training mission was very successful, and the groups requested more of the same to allow additional crews to practice inter-group operations before deploying overseas.

In April, the 315th altered its training program to comply with a change in XXI Bomber Command tactics. Between 24 March and 3 April 1945, General Curtis LeMay, Commander of XXI Bomber Command since January, ran four experimental missions to test the selective precision bombing capabilities of his APQ-13 radar-equipped B-29s. Unfortunately, the APQ-13 proved inadequate, and Gen. LeMay temporarily abandoned the effort. Instead, he directed his B-29 wings to methodically destroy Japanese urban industrial areas from greatly reduced altitudes. Subsequently, the 315th was advised to expect to conduct night, all-weather, precision radar bombing operations at 15,000 feet instead of 30,000 feet. The 315th modified its training program toward this new guidance and planned to keep a small headquarters staff at Peterson Field and in the Caribbean to oversee group training during the remaining weeks before deployment.

Back to Introduction

Back to Introduction and the Aircraft

On to The Service Groups

Content ©2003-2004, Larry Miller

ljmiller at charter dot net

August 9, 2005