315th Bomb Wing

The following is from the 315th Bomb Wing (VH) history book. It was researched and written by Major Ralph Swann as partial fulfillment of his requirements for graduation from the US Air Force Command and Staff College. It is "Adapted from Air Command and Staff Research Report 862460 entitled A Unit History of the 315th Bomb Wing, 1944-1946."

OPERATIONS

On 26 June, the 315th was charged with excitement as the wing prepared for its first mission against Japan's home islands. The field order specified a maximum wing effort against the Utsube River Oil Refinery at Yokkaichi. Every man was anxious to show what the 315th could do, and each flight crew member keenly felt the anxiety and tension of the occasion.

The Commanding General reflected this attitude at briefing for that first mission. In tones of under statement that underlined his emphasis. General Armstrong declared, "The 315th Bomb Wing is making history today. If this mission is successful, this raid will revolutionize aerial bombardment.' And every last man voiced an inward thought that he would do his best and then some if necessary to make it a success.

The many months of training, organization, inconvenience, and planning were about to be tested in combat.

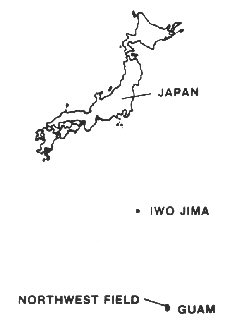

The pre-takeoff briefing was thorough. The operations officer briefed the mission using the 315th's special illuminated briefing technique. A night attack was planned to permit daylight takeoffs and landings as well as to compensate for the 315th's lightly armed B-29Bs. A 28- mile synchronous radar bombing run was planned at 15,000- 16,000 feet in compliance with the tactics established by Gen. LeMay's XXI Bomber Command. The mission's routing passed Iwo Jima before and after the strike and provided an emergency landing field, if needed. The intelligence officer described the enemy's defenses, and the weather officer gave the mission forecast. The crews then conducted their specialized briefing and reviewed the mission profile, route checkpoints, and radarscope photographs of the target. Everything was ready for Empire Mission 1.

Precisely at 1700 hours. Gen. Armstrong started his takeoff roll in the "Fluffy Fuz III" to lead the mission. Thirty-four B-29Bs from the 16th and 501st Bomb Groups followed him down the south runway at 1-minute takeoff intervals. Col. Gurney led the 16th's 15 B-29Bs while Col. Hubbard, in the "Fleet Admiral Nimitz," led 19 from the 501st. On takeoff the Superforts' engines became extremely hot as they strained to lift the bomb-laden planes into the tropical air. The crews found the steep cliff at the end of the south runway was well suited for B-29 operations, and they dropped down to just above the water to let the cooler air reduce the engine temperature before starting their climb. However, one 501st crew still had to turn back with engine trouble. Just prior to landfall at Japan, First Lieutenant Davis, 501st Bomb Group, also had an engine fail. Undeterred, he altered heading to complete a three-engine bombing attack against a target of opportunity at Kagata. The remaining 33 Superforts headed for the Utsube plant.

Navigator - Fluffy Fuz. William C. Leasure

As the crews started their bomb run, the weather conditions were ideal for radar bombing. The sky below was totally overcast and blinded the enemy's ground defenses. The APQ-7 Eagle radar easily penetrated the cloud cover and located the target at the mouth of the Utsube River two miles south of Yokkaichi. One Japanese fighter with its running lights on made a pass at Col. Gurney's aircraft but didn't fire a shot. Approaching the target, the antiaircraft fire was meager and inaccurate. The 33 Superforts crossed the target in a steady, single-file stream and dropped 223 tons of bombs on Utsube. After crossing the target, each crew turned sharply to change course, called a "breakaway," and headed homeward.

Two minutes after breakaway, the crew of the "Moldy Fig" nearly collided with another Superfort. First Lieutenant Ray J. Blaskey, the bombardier, spotted another B-29B about 100 feet away and yelled for the pilot, Lt. Leonard D. Jones, to dive to avoid a collision. The left scanner had been dispensing rope at the time and was thrown halfway through the camera hatch by the violent maneuver. Moments later the right scanner was knocked out briefly when he stepped into a hole and fell to the floor while trying to go rescue the left scanner. The right scanner quickly recovered and pulled the left scanner out of the hatch. The scanners administered first aid to each other and were all right. The crew of the "Moldy Fig" never discovered who they almost hit that night, or who was at fault in the near collision.

The 315th's first mission had mixed results. On the positive side, the wing completed its first mission and proved it was operational. There were no major injuries, and only one plane received minor damage to the right rear bomb-bay door. One 16th Bomb Group B-29B, commanded by First Lieutenant Whitted, ran low on fuel and landed at Iwo Jima. The remaining aircraft returned safely to Northwest Field; including Lt. Davis who flew all the way back to Guam with only three engines operating. On the negative side, the target was only partially destroyed. "Reconnaissance photos disclosed that 539,330 feet, or 30 percent, of the roof area was destroyed or damaged as a result of this mission. Many of the vital portions of the refinery were hit and seriously damaged." However, the refinery had not been knocked out, and another mission was needed to complete the job.

The 315th's first Empire mission highlighted the unique distance and weather problems complicating the strategic air campaign against Japan. First, the one-way distance from Guam to the Japanese mainland was more than 1,450 miles, or twice the distance for bombing missions in Europe. Secondly, Japan was situated between the continent of Asia and the broad Pacific Ocean and subject to unusual weather conditions. "Invariably, there were stacks of deep-bellied, stagnant clouds. Winds over Tokyo at high altitude probably were the strongest and most conflicting in the world." The high winds aloft over Japan were erratic in direction and generally from 100 to 175 miles per hour in velocity. These unusual winds drastically complicated the bombardier's task of lining up for the target and compensating for excessively high or slow ground speeds. Bombing accuracy also suffered because the winds adversely affected the flight path of the bombs falling to the target. Finally, the weather enroute to Japan over the vast stretch of water was frequently characterized by towering, powerful thunderstorms. However, "The Superfortress Supermen shrugged at the weather and drove their ships through the fronts to drop bombs either visually or by radar."

To deal with the unusual weather over the target, Gen. Armstrong decided to modify the bomb run procedure for Empire Mission 2. He planned to send an aircraft to the target a few minutes ahead of the wing's main force to broadcast wind drift information. The remaining crews could then apply sufficient corrections during the bomb run to compensate for the rapidly changing wind conditions, thereby improving bombing accuracy. Since the wind run aircraft would also drop bombs. Col. Hubbard took the assignment for this mission.

On 29-30 June, the 315th launched 36 B-29Bs to attack the Nippon Oil Company's plant at Kudamatsu. The Kudamatsu plant was one of the largest petroleum producers in Japan. Superforts from the 16th and 501st Groups launched in separate waves starting at 1811 hours using 45-second takeoff intervals. Shortly after takeoff, a 16th crew experienced engine trouble, jettisoned their bombs, and returned to Guam escorted by another B-29B. Meanwhile, the 501st, as the lead group, slowly climbed 8,000 feet while the 16th continued to 10,000 feet. One hundred miles prior to landfall at Japan, two more 501st crews had engine failures and terminated the mission. The remaining 32 Superforts climbed through a weather front to 15,000 feet and started their radar bombing run.

For the second time, the weather at the target was ideal to test radar bombing. A solid overcast hid the Kudamatsu refinery located west-southwest of Kure on the coast of Honshu Island. Col. Hubbard's crew flew ahead and reported a strong wind shift during their bomb run. Meanwhile, 17 enemy fighters approached the main wing force and began flying a parallel course as close as 500 feet. Since the fighters didn't attack, they may have been getting altitude checks for the antiaircraft batteries below. However, enemy flak activity was light. The crews used 1 minute bombing intervals and dropped 209 tons of 500-pound General Purpose (GP) bombs on Kudamatsu. All aircraft returned safely to Northwest Field and completed the mission with an average flying time of 14 hours and 56 minutes.

The bombing results for Empire Mission 2 were similar to the first mission. Photo-reconnaissance showed the Kudamatsu plant sustained only 5 percent total damage with a 45,000 square foot refining unit and several small storage tanks and buildings totally destroyed. The bomb impact pattern was to the right and long with the Haitachi Manufacturing Company, a locomotive factory located adjacent to the Kudamatsu plant, approximately 40 percent destroyed by bombs falling beyond the briefed target. Although the bombing results for the first two missions were somewhat disappointing, the 315th crews had a taste of combat and were proud of the damage they had inflicted on the Japanese Empire. They were eager to improve their performance in the month of July, Gen. Armstrong was too!

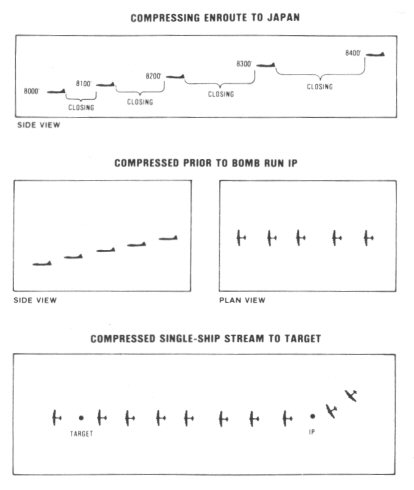

Gen. Armstrong directed his staff to improve the wing's bombing accuracy. After careful analysis of wing bombing procedures, the 315th's operations staff realized the European theater bomb run procedures being used by the wing were inappropriate for Japan. The shorter bombing runs by units in Europe and by the 315th in the States didn't provide enough time for the crews to compensate for the unique wind conditions over Japan. Thus, they decided a much longer bombing run was needed to give crews adequate time to apply the wind information being supplied by wind run aircraft and to lock-in on the target. On the other hand, they were concerned that a longer bomb run would also increase crew exposure time over the target and give the enemy more time to zero-in on the Superforts. Furthermore, they knew this exposure time problem would heighten as the wing increased in strength and dispatched more aircraft. While other bomber units relied on formation bombing to reduce exposure time, the 315th had to fly in a single-ship stream to align the APQ-7 radar with the target. Each 315th crew was one-on-one with the target and the enemy's defenses. Something was needed to improve their chances for survival on a longer bomb run.

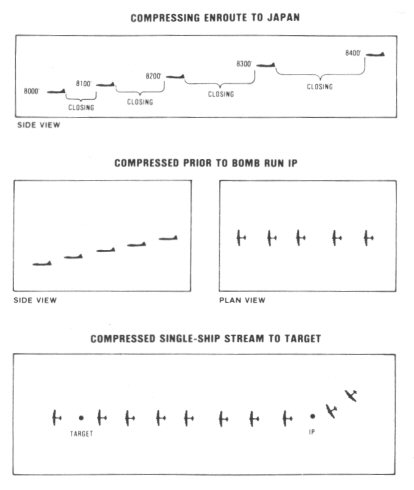

In response, Captain William C. Leasure, Gen. Armstrong's staff navigator and wing Tactical Plans Officer, developed a "compressibility" procedure to solve the problem. His procedure compensated for the lengthy B-29 takeoff period and allowed the flight crews to safely compress their aircraft interval during a longer bomb run. The key to his procedure was a method of aircraft cruise control the crews would use enroute to Japan.

We planned that each aircraft would fly at 100' elevation intervals, using the same indicated air speed for all; i.e., the first aircraft fly at 2,000' from Guam to the point where the climb was started to achieve bombing altitude prior to the IP; the second at 2,100'; the third at 2,200; etc. The True Air Speed factor of 2 percent increase over indicated [airspeed] per 1,000 feet, gave me the closure over a great distance that was necessary to compress the aircraft bombing times to perhaps 20 percent of the elapsed takeoff time outlined to match the needs.

The compressed stream of aircraft crossed the initial point (IP) at the planned altitude and maintained their compressed spacing to the target. Capt. Leasure's procedure increased aircraft compressibility during the longer bombing run and minimized flight crew exposure to enemy fire. Unfortunately, the group commanders opposed the longer bombing run and compressibility plans because of factors unknown and concern for the safety of their men. Gen. Armstrong listened to all the objections, but supported the plan by stating, "That's the way it will be." Consequently, the groups prepared to use Capt. Leasure's procedure on the next Empire mission.

Meanwhile, Lt. Rhodenhamel had to reveal the existence of his secret refrigerator to the 16th Bomb Group commander. Following Empire Mission 2, Lt. Rhodenhamel had taken bread from the mess hall and had to pass by Col. Sam Gurney on the way to his quonset hut. Col. Gurney said nothing, but within an hour he paid a visit to Lt. Rhodenhamel's Quonset and asked about the bread. Lt. Rhodenhamel confessed he had taken the bread and then promptly offered Col. Gurney a cold beer and a sandwich. Col. Gurney was surprised to see the refrigerator, but sat down and enjoyed the hearty snack. From then on, Lt. Col. Richard Kline, the 15th Squadron Commander, was always interested in why the 16th Group Commander was such a frequent visitor to Lt. Rhodenhamel's quonset.

Morale in the 315th improved dramatically in June. Living conditions were substantially better with prefabricated housing construction nearly completed and some of the permanent mess halls opened. The 16th and 331st Bomb Groups' newspapers, El Gecko and The Target, respectively, made their debut at Northwest Field in June. The 502nd's Special Services Section installed an ice cream machine and began making ice cream for the entire group on Sundays. The inauguration ceremony for the El Gecko Theater was followed by several live shows and nightly movies. On 28 June, the wing announced the installation of a new mail facility to improve mail services. A long list of eagerly awaited promotions was released at the end of the month. However, the biggest boost to morale was the reuniting of the wing's ground and air echelons and the start of combat operations against Japan.

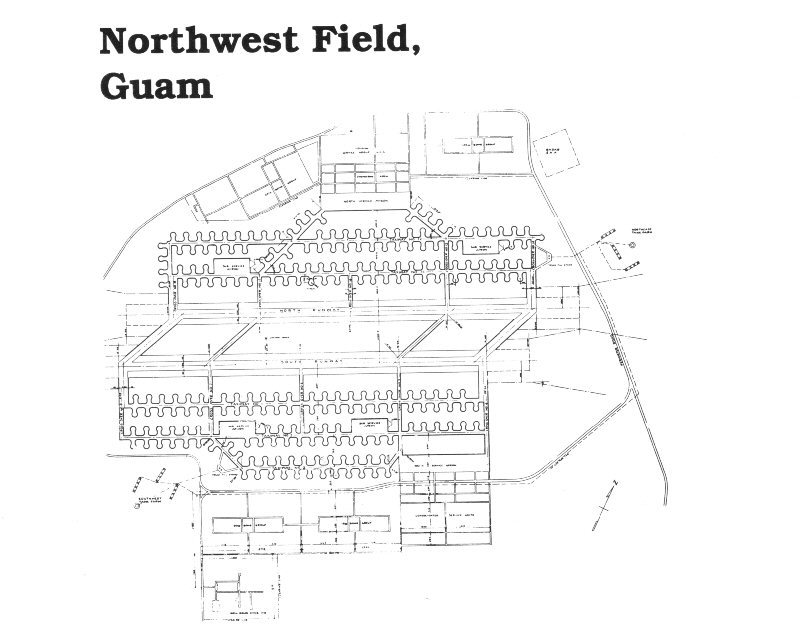

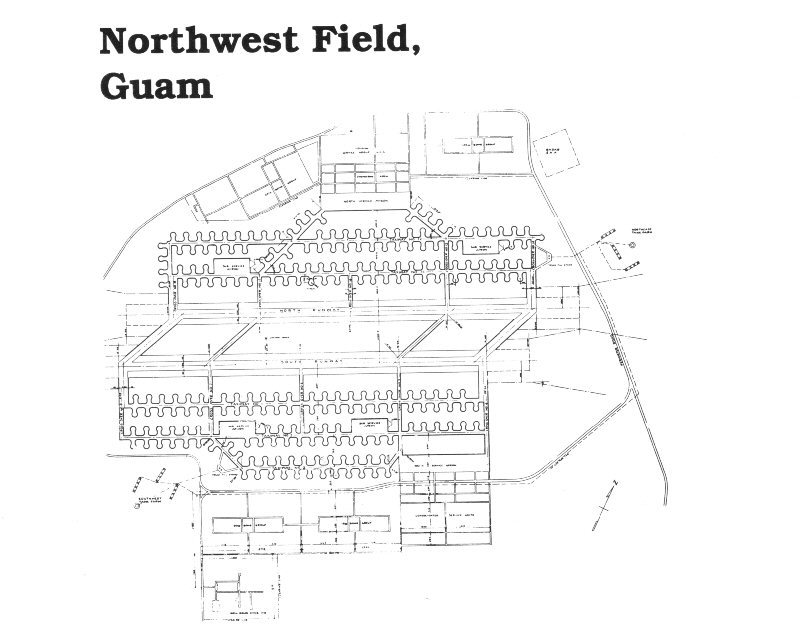

By the end of June, Northwest Field's airstrip was nearly finished. The south runway and service aprons were operational. The north runway was two-thirds finished and forecasted to be operational in early July. Most of the grading work on the north runway's taxi strips was completed and readied for hard surfacing in July. The wing needed the north runway and service strips completed to expedite the launching of its rapidly growing B-29B force.

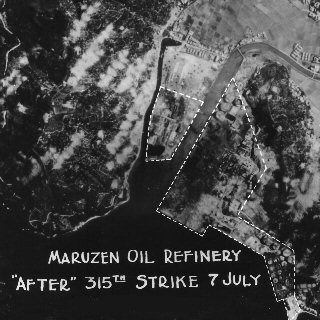

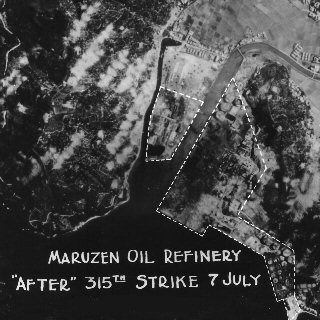

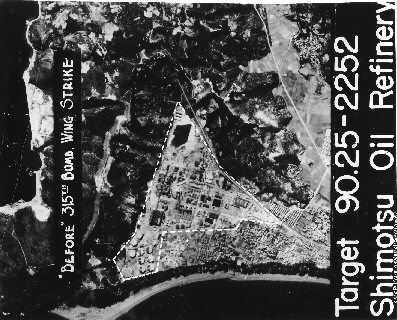

On 2-3 July, Col. Hubbard led Empire Mission 3 against the Maruzen Oil Refinery at Shimotsu. The plant was not only a major producer of aviation gasoline, lube oil, ordinary gasoline, and fuel oil, but it also had extensive oil storage facilities for the Japanese Navy. The wing launched 40 aircraft and 39 dropped their 500-pound GP bombs on the Maruzen refinery. The returning aircrews reported columns of smoke rising to 10,000 feet and thought they had leveled the target. However, reconnaissance photos showed only 5 percent of the plant was destroyed. Consequently, a follow up strike was scheduled for the night of 6-7 July.

On Empire Mission 4, Col. Hubbard led a force of 60 Superforts to restrike Maruzen. Col. Gurney led the 16th Bomb Group's element of 31 B-29Bs. As the B-29Bs approached Japan at 10,000-11,000 feet, 34 enemy fighters jumped them and made several attacks seeming to try to ram the Superforts. Col. Hubbard's crew flew ahead to bomb the target and to broadcast the wind data to the remaining wing force.

In the nose, the Norden bombsight indicators came together. Hubbard's red light flashed, indicating the bomb bay doors had snapped open. "Bombs away!" came the cry and the aircraft lifted as 10 tons of bombs headed for Maruzen. Hubbard swung right and down away from the target. His copilot, Major Gregory Hathaway, got the best view because he was on the inside of the turn as explosions erupted below and lit up the clouds. "We've hit pay dirt!" Greg shouted. "Of all the crap I've taken since I've been in the Army, it's paid off tonight."

Minutes later, 58 other Superfort crews located the target on radar, dropped their lethal bomb loads, and turned home ward leaving Maruzen engulfed in flames.

The reconnaissance photos for the Maruzen Mission proved its success. Photo analysis experts at XXI Bomber Command reported the Maruzen Oil Refinery was totally destroyed. Gen. LeMay's staff concluded that a force of 117 non-Eagle equipped B-29s would have been required to produce the same results as the 315th's smaller Eagle radar force. Gen. LeMay was so impressed he sent a congratulatory message to the 315th.

Successful strike is subject. I have just reviewed the post strike photography of your strike on target 1764, the MARUZEN Oil Refinery at SHIMOTSU, the night of 6/7 July. With a half-wing effort you achieved ninety-five percent destruction, definitely establishing the ability of your crew with the APQ-7 to hit and destroy precision targets, operating at night. This performance is the most successful radar bombing of the Command to date. Congratulations to you and your men.

Click on the photo for a larger view. Images courtesy of Mark Schroeder.

Gen. LeMay's praise reinforced the growing self-confidence and pride each man in the 315th had in his unit and its combat abilities. Thus, they were eager to repeat their accurate bombing performance on the next mission. Coincidentally, a new wing program was ready to ensure they would.

A radar operator training program was started to correct deficiencies noted in the first few Empire missions. Major problem areas identified included wind drift corrections for the bomb run, coordination between radar operators and bombardiers, and radar identification of landfall points. Training classes that included thorough radar film analysis were started to correct these problems and improve mission planning. In addition, a mockup of the APQ-7 was built so radar operators could practice in flight maintenance procedures.

While early radar operators were poorly trained, those in the 315th had the best training of all. Pre-mission briefings were so thorough that operators had to spend hours going over radar briefing material, including scope reconnaissance photos of the target, and they had to prove they could draw the details of the target from memory.

The training program was used to increase the radar bombing accuracy of crews already in combat and as a means to share their experiences with the newly arrived crews.

The 315th also implemented a new altimeter setting procedure to improve aircraft compressibility over the target. Altitude separation was a crucial factor for safely compressing aircraft over the heavily defended targets. Different methods of coordinating altimeter settings at mission takeoff briefings had been tried but proved lacking. Finally, the 315th's crew tried an altimeter setting of 29.92 inches (barometric)* for the entire flight except for takeoff and landing. This method proved highly successful and became the standard operating procedure for the wing's aircrews.

[*This altimeter setting procedure is used today in the United States' air traffic control system.]

For Empire Mission 5, the 315th revisited the Utsube River Oil Refinery on 9-10 July. The 331st provided 4 crews for its first mission against Japan and joined 60 crews from the 16th and 501st. Col. Peyton, the 331st Group Commander, led the crews of Captains Baughn and Goring and First Lieutenants Moore and Griffieon on the mission. Northwest Field's north runway was operational for the mission, and the wing's 64 Superforts launched at 30-second intervals. Approaching the coast of Japan, 50 enemy fighters were spotted, and two attacks were made. On one attack, First Lieutenant Maurer's crew exchanged fire with a fighter, but neither aircraft was hit. Flak over the target was moderate, and four aircraft suffered minor battle damage. Sixty-one Superforts reached the primary target and dropped 469 tons of GP bombs on Utsube with the 331st contributing 27 tons to the total. Aircraft compressibility was excellent with 50 aircraft crossing the target in 33 minutes. Except for two 16th Group B-29Bs which landed at Iwo Jima, all aircraft reached Northwest Field. However, one aircraft crashed and burned on the runway after its landing gear collapsed on landing. Fortunately, the crew survived. Photo-reconnaissance showed the raid successfully knocked the plant "out of commission for at least several months, if not completely beyond repair." While the 16th, 331st, and 501st were successfully striking Utsube, tragedy had struck the 502nd back at Guam.

Click on the photo for a larger view. Images courtesy of Mark Schroeder.

On the night of 9 July, one of the 502nd's flight crews crashed shortly after takeoff on a training strike to Truk. At 2300 hours, the first of ten 502nd crews launched from Northwest Field on the unit's first shakedown mission. The launch went smoothly until the last aircraft, commanded by First Lieutenant Wilkes, suddenly wavered in the air moments after takeoff and plunged into the sea 200 yards northeast of Guam. An LCI crew patrolling the coastline saw the aircraft explode. Immediately thereafter, personnel at Northwest Field heard a secondary explosion and saw a huge fireball light up the night sky. Air-sea rescue units searched the area thoroughly, but no survivors were found. "A piece of material containing the plane number was found which identified the crashed plane. A Mae West, 1 glove, and 4 green oxygen bottles were identified as accessories of the plane." Meanwhile, the 502nd's remaining airborne crews continued the Truk mission knowing their striking force had been reduced by one. The 502nd's first combat training strike against Truk proved successful but was marred by the loss of Lt. Wilkes' crew. The cause of the accident was unknown, but it may have been brought on by an engine malfunction.

The 315th's maintenance personnel faced a difficult challenge trying to keep the Superforts engines operational. Although the Wright Cyclone 3350 engines on the 315th's flyaway B-29Bs were far better than those on the aircraft used in training, they still had a lot of valve problems.

The 3350 was known for swallowing valves. It was a strange engine to troubleshoot because the same problem would not always give you the same indication. One day as the aircraft were taxiing out for a mission, we pulled an A/C out of the line-up because we could hear the familiar loud tapping noise as it went by. The engineer had no indication of a problem, and the pilot was furious because he wanted to make the mission. We soon found the problem, (zero) compression on one cylinder, which meant a cylinder change.

When the maintenance crews first arrived on Guam, they were authorized to change a maximum of three cylinders on an engine. However, in the summer of 1945 they received a TWX authorizing them to change all 18 cylinders, if necessary, because a labor strike at the stateside engine plant had severely disrupted the flow of replacement engines to the Pacific theater. This TWX dramatically increased the workload of the 315th's already overworked maintenance crews. The grueling work schedule was hard on all ground support personnel, and the men sought various outlets to relieve their tensions.

In July, the men of the 24th Air Service Group used their talents to improve morale by supplementing their beer rations. Finding something alcoholic to drink was not too hard for the flight crews, but the ground personnel's beer was rationed to two cans a week. With the help of some Seabees and Navy personnel, several members of the 24th built a homemade still and started making "Raisin Jack" and running off "white lightning." The procedure was an art form for several members who hailed from Kentucky and West Virginia, and their product sold for $20 a gallon. It was also 130 proof so the men used juice, water, or anything they could get to cut it. One night, someone spiked the water bag outside the 24th Headquarters Squadron barracks with Raisin Jack. As a result, many men were unable to report for duty the following day. First Sergeant Walter Bolding analyzed the problem and was the first to discover the cause of the epidemic. Thereafter, the morale of the 24th was usually higher than many of the other groups.

On 12-13 July, the 315th attacked the Kawasaki Petroleum Center. The same four 331st crews from the previous wing mission joined 58 crews from the 16th and 501 st for Empire Mission 6. In the primary target area, there were four separate, but adjacent, companies: Standard Oil, Rising Sun Oil, Nippon Oil, and Mitsui Products. Although the target was protected by heavy antiaircraft defenses, there was little flak due to heavy overcast skies. Thirty-eight enemy fighters were spotted, and two brief, but unsuccessful, assaults were made on the Superforts. Fifty-three B-29Bs dropped 452 tons of bombs on the target before turning homeward. In the raid, the target's tank storage capacity was moderately damaged while 27 percent of the total roof area was also damaged. The target was not totally destroyed and would have to be hit again.

Unfortunately, the 315th suffered two combat losses on the Kawasaki mission. Both B-29Bs and crews were from the 16th Bomb Group. Shortly after takeoff on the mission, First Lieutenant Milford Berry's crew developed three runaway propellers on their aircraft and were forced to ditch at sea approximately 125 miles north of Guam. At least five men of Crew 28 were known to have bailed out before the crash. Of these, three were picked up alive by surface rescue vessels, one was found dead, and the fifth man was never located. The other five crewmen apparently went down with their Superfort. In the second incident, First Lieutenant James C. Crim's crew completed their bombing run at Kawasaki but failed to return to Northwest Field. Lt. Crim and his crew were listed as missing; no word was ever received from the crew.

The three survivors of Lt. Berry's crew owed a special debt of gratitude to the 315th's Personal Equipment Sections. The wing's life support specialists not only maintained and stored flight crew lifesaving equipment, but they also provided emergency procedures training. Although the flight crews hoped they would never have to use their parachutes, life vests, or rubber rafts, they knew the dangers of the long over water combat missions.

Any aircrew member who has returned safely from the unenviable experience of 'ditching' must have taken time out to thank the Lord for his good fortune. But a sense of appreciation must have told him that he should have reserved a mental note of tribute to those men responsible for the condition of the lifesaving equipment -which made this 'ditching a success.

Each member of the wing's personal equipment sections had a tedious job of maintaining thousands of pieces of life support equipment in top working condition. They measured the success of their support efforts in the number of crew lives saved by the operable condition of the life support equipment they provided.

By early July, the 315th Wing staff was concerned about repeated reports of serious malfunctions with the APG-15 radar-directed tail turret system. Crew gunners had increasingly reported they were forced to recalibrate the APG-15 in flight even though maintenance personnel had calibrated the system perfectly prior to takeoff. In addition, the APG-15 frequently locked-on to a target without searching or would search but refuse to lock-on to a target. Fortunately, enemy fighter attacks had been light. However, intelligence reports indicated the Japanese were conserving their fighter forces and building strength to defend the home islands against an American invasion. Since the 315th's crews were sitting ducks for enemy fighter attacks without the APG-15 system, the wing staff wanted the problem corrected as soon as possible.

On Friday, 13 July 1945, the wing initiated Special Project EPR No. 1 to solve the APG-15 problem. Major William G. Pierce was assigned as director to accomplish the project's threefold purpose: (1) To place in combat readiness at once the APG-15 and related equipment in operational B-29 aircraft under this command; (2) To teach group personnel how to use this armament; and (3) To teach all B-29 gunners of these groups how to operate the equipment advantageously. A special group of people was selected to help Major Pierce, Dr. Vance Holdam from MIT, the designing engineer on the APG-15, was flown to Guam to help solve the maintenance difficulties encountered by every group in the 315th. Test flights were conducted using P-38 aircraft to make simulated attacks on B-29Bs to evaluate the APG-15 system and its operators. Training courses were developed and given to maintenance and flight crew personnel. The 315th's goal was to ensure that all personnel and equipment were fully prepared if, and when, the Japanese decided to use their remaining air power to counter the 315th's operations

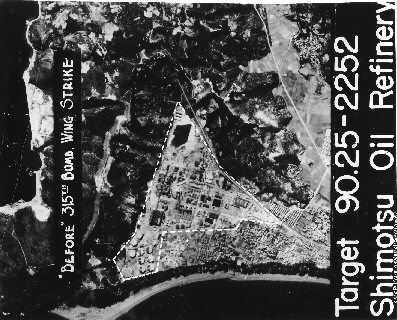

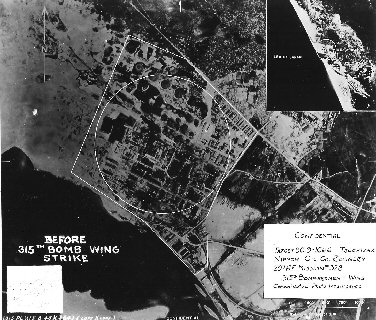

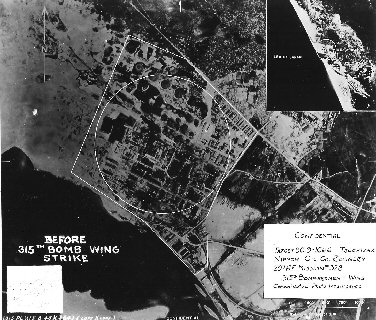

On 15-16 July, the 502nd Bomb Group got its baptism of fire on Empire Mission 7. The target for the mission was the Nippon Oil Refinery at Kudamatsu. Captains Hall, Woida, and Swartz and First Lieutenant Boulware led their 502nd crews on that unit's first combat mission. Col. Sanborn, the 502nd Group Commander, flew as an observer on Capt. Hall's aircraft. The 315th launched 71 Superforts for a return visit to the weakly defended Kudamatsu plant. An 85-mile bomb run was planned using a 1-minute bombing interval between aircraft. Two crews were sent ahead to act as weather scouts for the primary target and then completed a diversionary bombing attack on the Ube Coal Liquefaction Company. Enemy opposition was negligible, and 61 Superforts pounded Kudamatsu with 494 tons of bombs. All four 502nd aircraft bombed Kudamatsu, and Capt. Hall's crew split the target in half with 27 bombs. After bomb release, the crews broke left and headed to a turning point on northern Kyushu. They then cut across the eastern tip of Kyushu and headed for Guam via Iwo Jima. There were no casualties or aircraft losses for the mission.

Click on the photo for a larger view. Images courtesy of Mark Schroeder.

Damage reports from the Kawasaki raid showed the target was virtually destroyed. All the refinery units were damaged or destroyed, and there was also extensive damage done to the adjacent warehouse buildings and a crude oil tank farm.

341,000 barrels, or 85 percent of the original crude oil tank capacity (400,000 barrels) destroyed or damaged; 49,300 barrels or approximately 70 per cent of the original intermediate oil tank capacity (71,300 barrels) destroyed or damaged; 17,200 barrels or approximately 15 percent of the original refined oil tank capacity (115,700 barrels) destroyed or damaged; 2 oil bunkering piers on the south side of the refinery destroyed.

The wing's first raid with all four bomb groups participating was tremendously effective and set the stage for larger bombing strikes.

The 315th's Superforts were readily identified in combat by their distinctive external features and unit markings. The 18-foot APQ-7 Eagle radar antenna mounted beneath the fuselage and the single tail gun turret were unique to the 315th's B-29Bs. Each Superfort also had a large diamond symbol painted on the tail with one of four letters (B ,L,Y ,H) inscribed to identify the 16th, 331st, 501st, and 502nd Bomb Groups, respectively. Unfortunately, the wing's Superforts were also easily identified by the enemy on the ground.

The 315th's military police sent out a patrol to search for Japanese soldiers on 16 July. Six days earlier, security guards patrolling the jungle area east of Northwest Field had found evidence of recent Japanese habitation. Thus, a patrol was organized and sent into the designated sector. On the first day of the patrol, they killed four Japanese soldiers and wounded another who died later. "Two days later, another pair of enemy survivors were sent to accompany their ancestors." Although this patrol was successful, more Japanese soldiers were probably still at large on the island. As a result, two weapons carriers were equipped with 50-caliber machine guns and were used to guard against future reprisals by any remaining Japanese soldiers.

On 16 July, the 16th Bomb Group staff was reorganized. Lieutenant Colonel Castellotti, acting commander of the 16th, called a meeting of all officers at 1600 hours and made the following announcement:

As of 1330 this afternoon, I assumed command of this organization permanently...Col. Gurney will not be back. Where he is going, I cannot tell you. Bull can tell you that we have lost a hell of a fine officer. As far as his policies in training, organization, and discipline are concerned, they shall remain the same.

Lieutenant Colonel Collier H. Davidson assumed the 16th's Deputy Commander dudes. Major Zed S. Smith III was assigned to replace Lt. Col. Davidson as operations officer. Lt. Col. Castellotti concluded by praising the group staff for their past performance and stressed the importance of full cooperation between the group and wing staff personnel.

In July, there were also major changes to the organizational and command structure for strategic forces operating in the Pacific. With the end of the war in Europe, the Eighth Air Force was being converted to very heavy bombardment operations and scheduled to deploy to Okinawa. As a result, the United States Army Strategic Air Force (USASTAF) of the Pacific was established at Guam on 5 July to control and coordinate the pre-invasion combat operations of the Twentieth Air Force and the redeploying Eighth Air Force. On 16 July, the XXI Bomber Command officially became known as the Twentieth Air Force and headquartered at Guam with five B-29 wings, the 509th Composite Group, the Seventh Fighter Command, and the Guam Air Depot under its command. Thus, the USASTAF became the guiding force for the final assault on Japan with Twentieth Air Force carrying the load until the Eighth Air Force became operational.

Prior to takeoff on Empire Mission 10 on 26 July, Capt. Henry Dillingham's crew entertained two special guests. Mr. Walter Dillingham was on a special diplomatic mission to the Philippines and stopped at Northwest Field to see his son's crew takeoff on their combat mission. Mr. Dillingham was escorted by Gen. Giles, Commanding General of the Strategic Air Force, who also shook the hands with each of the crew members and wished them all luck on their upcoming mission. Capt. Dillingham's crew was one of eleven 402nd Bomb Squadron crews representing the 502nd Bomb Group's total B-29B striking force for this mission.

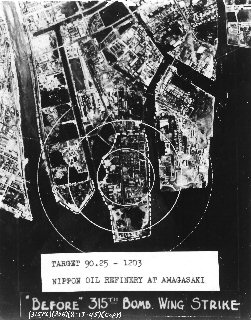

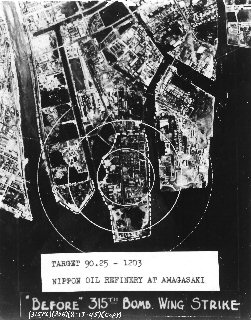

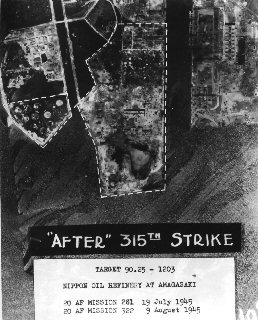

The 502nd's crews were assigned to strike a special target on Empire Mission 8. The wing's primary target was the Nippon Oil Refinery at Amagasaki. However, to test the 502nd's individual bombing accuracy, its special target was a small oil tank farm consisting of 10 oil tanks in an area measuring 850 feet by 1,000 feet and located just west of the main refinery. The "greenhorn" 502nd crews were determined to prove their bombing skills at Amagasaki. At the beginning of the bomb run, Captain Dipple's crew had an engine fail, but they continued the attack. Searchlights coned Captain Ramey's aircraft, and flak bursts ringed his Superfort. The crew promptly dropped rope to confuse the searchlights, and Capt. Ramey went to full power to escape the deadly fire. All eleven 502nd crews released their bombs on their special target, and the wing's total force of 83 B-29Bs crossed the target area in 34 minutes. The crews executed their breakaway maneuver and headed for Guam.

Post-mission photo-reconnaissance showed the wing attack on Amagasaki had mixed results. On the one hand, the 502nd wiped out the small oil tank farm with only two of the ten large oil tanks left undamaged, and those two tanks were empty. After the mission, Gen. Armstrong complimented the 502nd for its bombing results and stated, "I am proud to command a wing that has the 502nd Group in it." Unfortunately, the wing's 72 other aircraft had inflicted only minor damage to the main refinery area, and Amagasaki would have to be hit again.

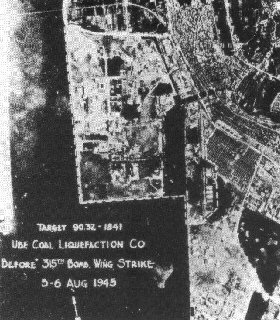

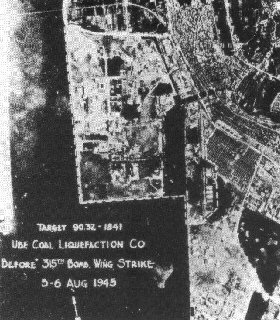

On 22-23 July, the 315th launched 82 aircraft on Empire Mission 9 to raid the Ube Coal Liquefaction Company. This important Japanese refinery was a leading producer of synthetic oil and a high priority target in a Japanese petroleum industry crippled by the U.S. naval blockade. Searchlight and flak activity over the target area was light and inaccurate. From an altitude of 12,000-13,000 feet, 74 Superforts dropped 637 tons of bombs on the primary target. Four other aircraft struck targets of opportunity due to radar malfunctions. All aircraft returned safely with only four receiving minor flak damage. Iwo Jima also proved its value on this mission with 19 of the wing's crews landing there. On this raid, 31 structures were damaged at the plant, but most of the refinery was still in operation.

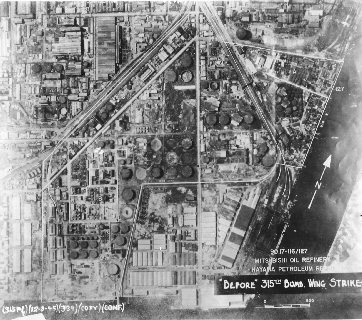

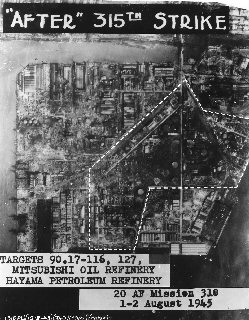

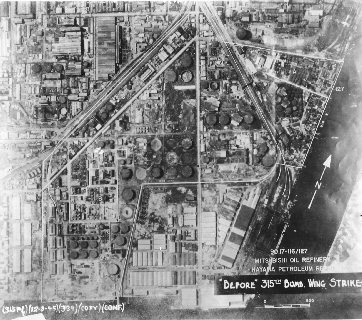

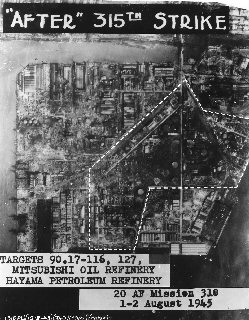

Empire Mission 10 was flown on the night of 25-26 July against the Hayama and Mitsubishi Oil Refineries. These targets were located in the heavily defended Yokohama-Kawasaki district just south of Tokyo, and the wing planned to use maximum compressibility for the attack. Of the 85 aircraft launched on the mission, 7 aborted prior to the target. The Japanese defenders took advantage of the clear night sky and used their searchlights to scour the sky for the Superforts. The flight crews dropped rope to confuse the enemy searchlights, but the defensive fire was relentless. Capt. Dillingham's aircraft was hit by flak and exploded in midair. It was a tough night in the target area with 13 aircraft damaged and Capt. Dillingham's crew lost in action. In the raid, 34 percent of the total storage tank capacity and 17 structures at the Hayama-Mitsubishi oil installations were destroyed or damaged. However, the joint target was still operative.

The dedicated efforts of the 315th's ground support personnel enabled the wing to fly its rapid succession of Empire missions. The sheet metal shops promptly repaired the battle damaged Superforts. The electronics sections achieved a 90 percent effectiveness rate for the APQ-7 radar equipment while the aerial photo section personnel kept the 0-5 radarscope camera operational. Maintenance work stands and towing tugs were in short supply so the engineering sections built their own stands and used jeeps to tow equipment. The armament and ordnance sections completed all bomb loading requirements on schedule despite shortages in B-7 bomb shackles and C-6 bomb hoists. The flight-line maintenance crews kept the aircraft fueled and completed the 50-, 100-, and 200-hour inspections. All 315th ground support personnel deserved a share of the credit for the wing's outstanding record during the first 10 Empire missions with 618 aircraft launched out of 636 scheduled.

The last Empire mission for the month of July was flown on 28-29 July against the Nippon Oil Refinery at Shimotsu. This plant was an important refiner of crude oil with large and modern facilities and good shipping and rail connections. The weather in the target area was ideal with overcast skies hampering the enemy's heavy searchlight and flak defenses. Of the 84 Superforts airborne, 78 saturated Shimotsu with 658 tons of bombs. The plant exploded, and the ensuing fires were the brightest the crews had ever seen.

[Reconnaissance] photos showed it was unnecessary to return to the refinery for in this one mission the target was almost completely destroyed. 927,000 barrels of the 1,246,000 barrel capacity were damaged while the 1,274,100 cubic foot gasometer capacity was almost completely destroyed. 69 percent of the 210,254 square foot area was destroyed. The target was thoroughly saturated with bombs and obliterated beyond repair.

Click on the photo for a larger view. Images courtesy of Mark Schroeder.

Target photo-reconnaissance also showed 60 percent of the wing's crews "placed their bomb salvo centers within 1,000 feet of the aiming point." As a result, the Shimotsu Oil refinery was erased from the priority target list by the 315th's pinpoint APQ-7 bombing accuracy.

The wing's photo lab personnel were extremely busy in July. During the month, they processed 1 1/2 million frames of radarscope photography film from the wing's nine Empire missions and numerous training sorties. Before each of these missions, the photo lab personnel carefully calculated the operating distances for the O-5 radarscope cameras to conserve the limited supply of valuable film. After the missions, they carefully analyzed the radar photographs to assess and validate the wing's target damage until post-strike photographs were obtained. In addition, the damage assessment photographs for the wing's Empire strikes in July also validated a photo lab developed technique for plotting aircraft bomb run tracks to determine bombing accuracy. The photo lab also ran a series of experiments and produced a suitable formula to prevent the fogging of photographic paper caused by the tropical climate. Finally, the photo lab completed the ordinary photo work in the public relations, identification, historical, and other related fields of ground activity.

Likewise, the 315th's Weather Section worked at a hectic pace in July. The month's stepped up radar photography, training, and Empire missions taxed the weather section to provide timely and accurate forecasts. In response, the weather section developed a special weather display to brief flight crews. The display used miniature cutouts of weather symbols treated with luminescent paints to depict forecasted weather conditions for the missions. Flight crews reported the new technique vividly portrayed the weather information and made it easier to remember the data on the long Empire missions.

For its first mission in August, the 315th planned Empire Mission 12 as a large scale raid against three previously bombed targets. The mission plan split the wing's B-29Bs into two forces to strike three adjacent targets in the heavily defended Kawasaki area south of Tokyo. One force would attack the Kawasaki Petroleum Center previously raided during Empire Mission 6 on 12 July. Meanwhile, the other force would concentrate on the Hayama and Mitsubishi Oil Refineries partially destroyed on 25 July during Empire Mission 10. Bombing altitude for the mission would be 15,000-16,000 feet. Since these facilities had already claimed 315th aircraft and lives, the flight crews were apprehensive but eager to knock them out.

Click on the photo for a larger view. Images courtesy of Mark Schroeder.

On 1-2 August, the 315th launched 130 Superforts for Empire Mission 12. Colonel William A. Miller, wing Deputy Chief of Staff, flew with First Lieutenant Larson's crew, 502nd Bomb Group, and led the entire wing off on the mission. The weather in the target area ranged from clear to 9/10 thin overcast skies. Two enemy fighters attacked First Lieutenant Ethier's aircraft but missed. An estimated 130 blue and green searchlights blanketed the skies, and antiaircraft fire was medium to heavy. Two aircraft sustained heavy flak damage while 13 other received minor damage.

One plane, H-5, commanded by Captain Woida, received major damage. The number one engine was shot out, fuel cells and gas lines were damaged, and other damage was done to the bomb-bay doors, wing, and other surfaces of the plane. It landed at Iwo, and the crew returned in a plane of the 16th Bomb Group which had previously been left at Iwo for repairs.

Captain Woida's aircraft was one of five forced to land at Iwo with heavy battle damage or engine trouble. The crews reported they had left the Kawasaki Petroleum Center and Hayama-Mitsubishi refineries engulfed in flames and were confident the targets had been destroyed.

The 315th's raid on the Kawasaki area was part of the largest single-day bombing effort by Twentieth Air Force during World War II. On 1 August, Twentieth Air Force dispatched 836 B-29s to bomb a variety of Japanese targets. Of these, 784 reached and bombed their assigned targets, including 120 Superforts from the 315th which dropped 1,025 tons of bombs on the Kawasaki targets. The damage report for the Kawasaki attack listed the Kawasaki Petroleum Center as "practically inoperative" while the Hayama-Mitsubishi refineries received "crippling damage" with 40 percent of the primary structures destroyed. Five other industrial installations were also struck and severely damaged. Consequently, the three Kawasaki plants were useless to the enemy.

On 5-6 August, the 315th flew its most spectacular mission, an attack on the Ube Coal Liquefaction Company. This target had been partially destroyed during a previous wing attack on 22-23 July. On this return visit, the wing launched 113 aircraft and 108 attacked the primary target with 938 tons of bombs.

The damage assessment was not available until 22 August, but it revealed a spectacular bombardment job. The refining units of the plant were 100 percent destroyed or damaged, and 80 per cent of the stores and workshops were destroyed or damaged. In addition, 50 percent of the (adjacent) Iron Works Co. had been damaged.

Furthermore, the nearby dikes protecting the Ube plant from the sea were hit by bombs. The target photo-interpreter who analyzed the damage sent a special post-strike photograph to Admiral Nimitz with a note attached reporting, "Target destroyed and sunk." In a letter of commendation to the Army Air Force commanders, Admiral Nimitz remarked that it was the first time bombers had ever sunk a factory.

Click on the photo for a larger view.

On the Ube raid, Crew 1102, 502nd bomb Group, aborted their takeoff but still completed the mission. Their takeoff was normal through 65 miles per hour, and Second Lieutenant John T. Newburg, the copilot, continued to call the increasing takeoff speeds. Suddenly, he shouted that engine number three had lost power, and Captain Horatio W. Turner III, the aircraft commander, promptly aborted the takeoff. As their aircraft rapidly approached the end of the runway, Capt. Turner told his copilot to get on the brakes with him while he pulled the emergency brake handles with his right hand. In succession, the left and right scanners reported the wheels were on fire as smoke poured from the overheated brakes. The aircraft ran off the end of the runway and onto the coral overrun, heading straight for a 50-foot-high bank. Capt. Turner described his instinctive reaction to avoid a collision.

Luck was with us. I felt some brake just as we were getting really close to the embankment. I stood on the left brake and let the airplane ground loop around the locked wheel. We cleared the embankment and were able to taxi out of the coral overrun and back along the runway and taxiway to the ramp. When I climbed out of the plane, my flying suit was wringing wet.

Maintenance promptly repaired the engine, found the cooled down brakes were operable, and topped the aircraft off with fuel. Capt. Turner and his crew launched again less than an hour after their aborted takeoff and flew the mission as "Tail End Charlie." They reached Ube and dropped their bomb load on the target. They were the last crew to return to Guam at 1140 hours on 6 August with a flight time of 15 hours and 25 minutes.

Meanwhile, Colonel Paul Tibbets and his 509th Composite Group crew had dropped the world's first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. After his bombardier released the atomic bomb at 0815 hours (Hiroshima time) on 6 August, Col. Tibbets immediately racked his aircraft, the "Enola Gay," into a sharp 150-degree turn to escape the impending blast. The bomb exploded less than a minute later, and a blinding light filled the sky. A huge, dark mushroom cloud erupted over Hiroshima, and 4 1/2 miles of the city were leveled. More than 71,000 of Hiroshima's 245,000 population died instantly. However, the Japanese government did not surrender following the attack. Three days later Major Sweeney, flying in "Bock's Car," led another 509th crew to drop a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki. News of the devastating new weapon spread rapidly through the Pacific, and the 315th finally learned the well-kept secret mission of its former subordinate unit. Everyone waited to see if the Japanese would finally call it quits. They didn't, and the 315th prepared for another mission.

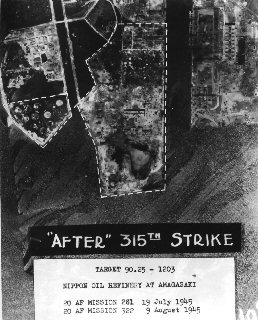

Empire Mission 14 was a return strike to the Nippon Oil Refinery at Amagasaki on 9-10 August. In the target area, there were a large number of Japanese fighter aircraft. However, only one made what might have been an attempt to ram First Lieutenant Pananes' aircraft and came within 15 feet. Flak activity was moderate to heavy with 11 Superforts receiving minor damage. Of the 109 B-29Bs launched, 97 dropped 918 tons of bombs on Amagasaki.

Click on the photo for a larger view. Images courtesy of Mark Schroeder.

Late photo reports said the target was almost completely destroyed. Damage was well distributed. In the tank area, only two tanks remained undamaged. Synthetic oil plants showed damage to a gasometer, four buildings, and a sulphur removal unit. In the refinery area, four refining units and 30 tanks were destroyed. In addition, nine other tanks and 25 buildings were damaged.

The 315th finished the job it had started at Amagasaki on Empire Mission 8 and left one more Japanese oil refinery in ruins.

The 315th's armament personnel performed their most remarkable feat for Empire Mission 15. The wing scheduled 145 Superforts to carry a payload of smaller 100- and 250-pound bombs for the mission. Unfortunately, the armorers had to load the 100-pound bombs by hand because the mechanical bomb hoists were designed for larger bombs. The armorers worked tirelessly on the sweltering flight line and in the over-hot bomb bays to complete the monumental task. To load the 16th Bomb Group's 38 Superforts, "Approximately 80 men worked for 17 hours lifting the bombs into place and after the task had been accomplished many were so tired they were unable to raise their arms above their shoulders." Thanks to the armorers' remarkable efforts, the 315th's B-29Bs were ready to deliver over 12,000 bombs to Japan.

On the night of 14-15 August, the 315th conducted its longest and largest raid of the war. The target for Empire Mission 15 was the Nippon Oil Refinery at Tsuchizaki on the northern coast of Honshu Island, a round trip distance of 3740 statute miles. Gen. Armstrong led the mission and launched at 1637 hours. However, some of the other crews, including Col. Hubbard's, were temporarily delayed on the ground.

When his (Hubbard's) airplane was out on the runway, a jeep drove up and an officer signaled to cut engines. Once this was done the officer climbed into the cockpit and said 'Admiral Nimitz says the war is over! Shortly afterward, another jeep rushed up and the driver yelled, 'Get going! LeMay hasn't received word that the war is over.

Postponed for several days by Japanese-American peace negotiations, the wing's maximum effort mission was finally underway.

Enroute to the target, the skies were full of B-29s. Approaching the coast of Japan, the 315th's crews saw hundreds of homeward bound B-29s. Col. Hubbard and other aircraft commanders turned their landing lights on to avoid a collision in the traffic jam above Honshu Island. Although 9 wing aircraft aborted the mission, 134 B-29Bs approached the lightly defended target at 10,000-12,000 feet and began their radar bombing run. The Superforts crossed the Tsuchizaki plant and dropped 954 tons of bombs on the target. Huge fires and dense smoke covered the refinery as the 315th's crews turned to start the long journey to Northwest Field.

Before the last 315th B-29B landed at Guam on the morning of 15 August, the war was over. President Truman had announced the unconditional surrender of Japan, and the returning crews heard the news over their radios. Thus, the 315th had inflicted the final bombing damage to the Japanese Empire with the last bombs away at 0339 hours, 15 August 1945. Captain Dan Trask's crew, 502nd Bomb Group, was the last to takeoff on Empire Mission 15 and was the last to land 16 hours and 45 minutes later. His crew and aircraft, "The Uninvited," immediately "received a publicity spread as the last plane over the Empire during the War."

Click on the photo for a larger view. Images courtesy of Mark Schroeder.

Results of photo-interpretation of damage brought now familiar words: 'Almost completely destroyed or damaged.' Photographs disclosed that no portion of the target was untouched. The three refining units were a tangled mess of wreckage, the main power plant still standing, but seriously hit. More than 66 per cent of the tank capacity was destroyed. Lesser installations, including the workers' barracks, were destroyed.

The bombing results were particularly impressive for the longest nonstop combat mission ever flown.

Back to Introduction

Back to The Pacific Theater

On to The War is Over

Content ©2003-2004, Larry Miller

ljmiller at charter dot net

August 9, 2005